You

Only Click Twice: FinFisher’s Global Proliferation

March 13, 2013

Bài được đưa lên

Internet ngày: 13/03/2013

Các tác giả:

Morgan Marquis-Boire, Bill Marczak, Claudio Guarnieri, and John

Scott-Railton.

Bài này mô tả các

kết quả của một cuộc quét Internet toàn cầu toàn diện

đối với các máy chủ chỉ huy kiểm soát của phần mềm

giám sát FinFisher. Nó cũng chi tiết sự phát hiện của

một chiến dịch sử dụng FinFisher tại Ethiopia được sử

dụng để nhằm vào những cá nhân có liên quan tới một

nhóm đối lập. Hơn nữa, nó đưa ra sự xem xét của một

ví dụ FinSpy Mobile được thấy trong hoang dại, dường

như đã được sử dụng tại Việt Nam.

Tóm tắt các phát

hiện chính

- Chúng tôi đã thấy các máy chủ chỉ huy và kiểm soát đối với các cửa hậu FinSpy, một phần của “giải pháp giám sát ở xa” FinFisher Quốc tế Gamma, trong tổng số 25 nước: Úc, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Brunei, Canada, Cộng hòa Séc, Estonia, Ethiopia, Đức, Ấn Độ, Indonesia, Nhật, Latvia, Malaysia, Mexico, Mông Cổ, Hà Lan, Qatar, Serbia, Singapore, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, Anh, Mỹ và Việt Nam.

- Một chiến dịch FinSpy tại Ethiopia sử dụng các bức ảnh của Ginbot 7, một nhóm đối lập người Ethiopia, như là manh mối để lây nhiễm cho những người sử dụng. Điều này tiếp tục chủ đề của các triển khai FinSpy với những chỉ thị mạnh nhằm đích có động lực chính trị.

- Có bằng chứng mạnh của một Chiến dịch FinSpy Mobile Việt Nam. Chúng tôi đã thấy một mẫu FinSpy Mobiel Android trong hoang dại với một máy chủ chỉ huy và kiểm soát tại Việt Nam mà cũng trích lọc các thông điệp văn bản đối với một số lượng điện thoại địa phương.

- Những phát hiện đó kêu gọi câu hỏi nêu ra của Gamma International rằng các máy chủ được nói trước đó từng không phải là một phần của dòng sản phẩm của họ, và rằng các bản sao được phát hiện trước đó của các phần mềm của họ hoặc đã bị ăn cắp hoặc sao bản demo.

1. Nền tảng và giới

thiệu

FinFisher

là một dòng các phần mềm giám sát và thâm nhập từ xa

được Gamma International GmbH có trụ sở ở Munich phát

triển. Các sản phẩm FinFisher được đưa ra thị trường

và được Nhóm Gamma có trụ sở ở Anh bán chỉ riêng cho

các cơ quan ép tuân thủ luật và tình báo1. Dù

được chào như một bộ “can thiệp hợp pháp” cho việc

giám sát tội phạm, FinFisher đã giành được trạng thái

hiển nhiên ai cũng biết vì nó từng được sử dụng

trong các cuộc tấn công có chủ đích chống lại những

người tham gia chiến dịch quyền con người và các nhà

hoạt động xã hội đối lập tại các quốc gia với các

hồ sơ quyền con người2 đáng nghi ngờ.

Vào cuối tháng

7/2012, chúng tôi đã

xuất bản các kết quả của một cuộc điều tra

trong một chiến dịch thư điện tử đáng ngờ nhằm vào

các nhà hoạt động xã hội ở Bahrain3. Chúng

tôi đã phân tích những tệp đính kèm và đã phát hiện

rằng chúng có chứa phần mềm FinSpy, sản phẩm giám sát

từ xa FinFisher. FinSpy chụp thông tin từ một máy tính bị

lây nhiễm, như các mật khẩu và các cuộc gọi Skype, và

gửi thông tin tới một máy chủ chỉ huy và kiểm soát

(C2) FinSpy. Các tệp gắn kèm chúng tôi đã phân tích đã

gửi các dữ liệu tới một máy chủ chỉ huy và kiểm

soát nằm trong Bahrain.

Phát hiện này đã

tạo động lực cho các nhà nghiên cứu tìm kiếm các máy

chủ chỉ huy & kiểm soát khác để hiểu FinFisher có

thể được sử dụng rộng rãi như thế nào. Claudio

Guarnieri tại Rapid7 (một trong những tác giả của báo cáo

này) từng là người đầu tiên tìm kiếm các máy chủ

đó. Ông đã lần ra dấu vết máy chủ ở Bahrain và đã

xem dữ

liệu quét Internet lịch sử để nhận diện các máy

chủ khác trên thế giới mà đã trả lời cho dấu vết y

hệt đó. Rapid7 đã xuất bản danh sách các máy chủ này,

và đã mô tả kỹ thuật lấy dấu vết của chúng. Các

nhóm khác, bao gồm cả CrowdStrike

và SpiderLabs

cũng đã phân tích và đã xuất bản các báo cáo về

FinSpy.

Ngay lập tức sau xuất

bản đó, các máy chủ hình như đã được cập nhật để

tránh sự dò tìm dấu vết của Rapid7. Chúng tôi đã phát

minh ra một kỹ thuật lần dấu vết khác và đã quét các

phần của Internet. Chúng tôi đã khẳng định các kết

quả của Rapid7, và cũng đã thấy vài máy chủ mới, bao

gồm một chiếc trong Bộ Truyền thông của Turkmenistan.

Chúng tôi đã xuất bản danh sách các máy chủ vào cuối

tháng 8/2012, bổ sung thêm vào một

phân tích các phiên bản điện thoại di động của

FinSpy. Các máy chủ FinSpy hình như đã được cập nhật

một lần nữa vào tháng 10/2012 để vô hiệu hóa kỹ

thuật lần dấu vết mới hơn này, dù nó từng không bao

giờ được mô tả công khai.

Dù

vậy, thông qua phân tích các mẫu đang tồn tại và quan

sát các máy chủ chỉ huy & kiểm soát, chúng tôi đã

xoay xở đếm nhiều hơn các phương pháp lần dấu vết

và tiếp tục khảo sát của chúng tôi về Internet đối

với phần mềm giám sát này. Chúng tôi mô tả các kết

quả trong bài viết này.

Các nhóm xã hội dân

sự đã thấy lý do để lo lắng theo những phát hiện đó,

khi họ chỉ ra sự sử dụng các sản phẩm FinFisher của

các quốc gia như Turkmenistan và Bahrain với các hồ sơ có

vấn đề về các quyền con người, sự minh bạch và qui

tắc của luật. Trong một trả lời hồi tháng 08/2012 cho

một bức thư từ NGO Privacy International có trụ sở ở

Anh, Chính phủ Anh đã phát hiện rwangf tị những thời

điểm không xác định trong quá khứ, nó đã kiểm tra một

phiên bản của FinSpy, và đã liên hệ với Gamma rằng một

giấy phép có thể được yêu cầu để xuất khẩu phiên

bản đó ra ngoài EU, Gamma đã từ chối một cách lặp đi

lặp lại các liên quan tới phần mềm gián điệp và các

máy chủ đã bị nghiên cứu của chúng tôi phát hiện,

nói rằng các máy chủ được các cuộc quét của chúng

tôi dò tìm ra là “không … từ dòng sản phẩm

FinFisher”4. Gamma cũng nói rằng phần mềm

gián điệp đó đã gửi cho các nhà hoạt động xã hội

ở Bahrain từng là một phiên bản demo FinSpy “cũ”, bị

ăn cắp trong quá trình trình diễn sản phẩm.

Tháng 02/2013, Privacy

International, Trung tâm châu Âu về Hiến pháp và Quyền con

người ECCHR (European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights),

Trung tâm của Bahrain về Quyền con người, Bahrain Watch, và

Reporters Without Borders (Các nhà báo Phi Biên giới) đã

đệ trình một khiếu nại với Tổ chức Hợp tác

Kinh tế và Phát triển (OECD), yêu cầu rằng cơ quan này

điều tra liệu Gamma có vi phạm các Chỉ dẫn của OECD

đối với các Doanh nghiệp Đa quốc gia bằng việc xuất

khẩu FinSpy sang Bahrain. Khiếu nại đã gọi các tuyên bố

trước đó của Gamma là khả nghi, lưu ý rằng ít nhất 2

phiên bản khác (4.00 và 4.01) của FinSpy đã được thấy

tại Bahrain, và rằng máy chủ chủ Bahrain từng là một

sản phẩm FinFisher và từng có khả năng nhận các bản

cập nhật từ Gamma. Khiếu nại này, như được Privacy

International đưa ra nó rằng Gamma:

- không tôn trọng các quyền con người của những người bị ảnh hưởng bởi cách hoạt động [của nó] được quốc tế thừa nhận

- đã gây ra và đóng góp vào những ảnh hưởng tới quyền con người trái ngược trong quá trình các hoạt động [của nó]

- không ngăn chặn và làm giảm nhẹ những ảnh hưởng tới quyền con người trái ngược có liên quan tới các hoạt động và các sản phẩm [của nó], và không giải quyết các ảnh hưởng như vậy ở những nơi mà chúng đã xảy ra

- không triển khai sự siêng năng phù hợp (bao gồm sự siêng năng về quyền con người); và

- không triển khai một cam kết chính sách tôn trọng các quyền con người.

Theo báo

cáo gần đây, Cảnh sát Liên bang Đức dường như có

các kế hoạch mua và sử dụng bộ các công cụ FinFisher

nội bộ bên trong nước Đức5. Trong khi đó,

những phát hiện của nhóm chúng tôi và các nhóm khác

tiếp tục minh họa sự nở rộ toàn cầu các sản phẩm

của FinFisher. Nghiên cứu tiếp tụ phát hiện các trường

hợp đáng lo lắng về FinSpy tại các nước với các hồ

sơ theo dõi các quyền con người buồn thảm, và các chế

độ đàn áp chính trị. Gần đây nhất, công việc của

Bahrain

Watch đã khẳng định sự hiện diện của một chiến

dịch FinFisher của người Bahrain, và xa hơn các tuyên bố

công khai đầy mâu thuẫn của Gamma. Bài viết này bổ

sung thêm vào danh sách bằng việc đưa ra một danh sách

cập nhật các máy chủ chỉ huy và kiểm soát của FinSpy,

và mô tả các mẫu phần mềm độc hại FinSpy trong hoang

dã xuất hiện đã được sử dụng để nhằm vào các

nạn nhân tại Ethiopia và Việt Nam.

Chúng tôi trình bày

những phát hiện được cập nhật đó trong hy vọng rằng

chúng tôi sẽ khuyến khích hơn nữa các nhóm xã hội dân

sự và các cơ quan điều tra có năng lực tiếp tục sự

soi xét của họ đối với các hoạt động của Gamma, phù

hợp với các vấn đề kiểm soát xuất khẩu, và vấn đề

nở rộ toàn cầu và không được điều chỉnh của các

phần mềm độc hại giám sát.

Hình 1. Bản đồ nở

rộ toàn cầu của FinFisher (Xem hình ảnh ở phần tiếng

Anh bên dưới)

2.

FinFisher: Quét toàn cầu được cập nhật

Khoảng tháng 10/2012,

chúng tôi đã quan sát thấy rằng hành vi của các máy chủ

FinSpy đã bắt đầu thay đổi. Các máy chủ đã dừng

phản ứng với sự lần dấu vết của chúng tôi, nó đã

khai thác một góc lượn trong giao thức có dây của FinSpy

có thể phân biệt được. Chúng tôi tin tưởng rằng điều

này chỉ ra rằng Gamma hoặc đã thay đổi một cách độc

lập giao thức FinSpy, hoặc đã có khả năng xác định

các phần tử chính của dấu vết của chúng tôi, dù nó

không bao giờ từng phát hiện được một cách công khai.

Trong

sự bùng lên của cập nhật hình như này đối với các

máy chủ chỉ huy & kiểm soát FinSpy, chúng tôi đã chế

ra một sự lần dấu vết mới và đã tiến hành một

cuộc quét Internet đối với các máy chủ chỉ huy &

kiểm soát FinSpy. Sự quét này mất khoảng 2 tháng và có

liên quan tới việc gửi hơn 12 tỷ gói. Sự quét mới của

chúng tôi đã nhận diện tổng số 36 máy chủ FinSpy, 30

trong số đó là mới và 6 trong số đó chúng tôi đã thấy

trong quá trình quét trước đó. Các máy chủ đã hoạt

động tại 19 nước khác nhau. Trong số các máy chủ

FinSpy chúng tôi đã thấy, 7 chiếc ở các nước chúng tôi

chưa từng thấy trước đó.

Các nước mới

Canada, Bangladesh, Ấn

Độ, Malaysia, Mexico, Serbia, Vietnam

Trong cuộc quét gần

đây nhất, 16 máy chủ mà chúng tôi trước đó đã thấy

còn chưa chỉ ra. Chúng tôi nghi ngờ rằng sau các cuộc

quét trước đó của chúng tôi được xuất bản, các nhà

vận hành đã chuyển chúng đi. Nhiều trong số các máy

chủ đó đã bị đánh sập hoặc tái định vị sau xuất

bản các kết quả trước đó, nhưng trước hình như bản

cập nhật tháng 10/2012. Chúng tôi không còn thấy các máy

chủ FinSpy tại 4 nước nơi mà việc quét trước đó đã

nhận diện được chung (Brunei, UAE, Latvia và Mông Cổ).

Tổng cộng, các máy chủ FinSpy hiện hành, hoặc đã từng

hiện diện, tại 25 quốc gia.

Úc, Bahrain, Bangladesh,

Brunei, Canada, Cộng hòa Séc, Estonia, Ethiopia, Đức, Ấn Độ,

Indonesia, Nhật, Latvia, Malaysia, Mexico, Mông Cổ, Hà Lan,

Qatar, Serbia, Singapore, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, Anh, Mỹ

và Việt Nam.

Quan trọng là, chúng

tôi tin tưởng rằng danh sách các máy chủ của chúng tôi

còn chưa đầy đủ vì sự đa dạng rộng lớn các cổng

được các máy chủ FinSpy sử dụng, cũng như các nỗ lực

khác được che đậy. Hơn nữa, sự phát hiện của một

máy chủ chỉ huy và kiểm soát FinSpy ở một quốc gia

được đưa ra không phải là chỉ số đủ để kết luận

sử dụng FinFisher của các cơ quan ép tuân thủ luật hoặc

tình báo của nước đó. Trong một số trường hợp, các

máy chủ đã thấy chạy trong các cơ sở được các nhà

cung cấp dịch vụ đặt chỗ (hosting) cung cấp mà có thể

được các tác nhân từ bất kỳ quốc gia nào mua.

Bảng dưới đây chỉ

ra các máy chủ FinSpy được dò tìm ra trong cuộc quét mới

nhất của chúng tôi. Chúng tôi liệt kê địa chỉ IP đầy

đủ các máy chủ từng trước đó được phát hiện. Đối

với các máy chủ tích cực mà còn chưa được phát hiện

công khai, chúng tôi liệt kê chỉ 2 bộ 8bit đầu. Việc

đưa ra các địa chỉ IP hoàn chỉnh trong quá khứ đã

không chứng minh được là hữu ích, khi mà các máy chủ

đã nhanh chóng bị đánh sập và tái định vị.*

|

IP

|

Người vận hành

|

Định tuyến tới nước

|

|

117.121.xxx.xxx

|

GPLHost

|

Australia

|

|

77.69.181.162

|

Batelco ADSL Service

|

Bahrain

|

|

180.211.xxx.xxx

|

Telegraph & Telephone Board

|

Bangladesh

|

|

168.144.xxx.xxx

|

Softcom, Inc.

|

Canada

|

|

168.144.xxx.xxx

|

Softcom, Inc.

|

Canada

|

|

217.16.xxx.xxx

|

PIPNI VPS

|

Czech Republic

|

|

217.146.xxx.xxx

|

Zone Media UVS/Nodes

|

Estonia

|

|

213.55.99.74

|

Ethio Telecom

|

Ethiopia

|

|

80.156.xxx.xxx

|

Gamma International GmbH

|

Germany

|

|

37.200.xxx.xxx

|

JiffyBox Servers

|

Germany

|

|

178.77.xxx.xxx

|

HostEurope GmbH

|

Germany

|

|

119.18.xxx.xxx

|

HostGator

|

India

|

|

119.18.xxx.xxx

|

HostGator

|

India

|

|

118.97.xxx.xxx

|

PT Telkom

|

Indonesia

|

|

118.97.xxx.xxx

|

PT Telkom

|

Indonesia

|

|

103.28.xxx.xxx

|

PT Matrixnet Global

|

Indonesia

|

|

112.78.143.34

|

Biznet ISP

|

Indonesia

|

|

112.78.143.26

|

Biznet ISP

|

Indonesia

|

|

117.121.xxx.xxx

|

GPLHost

|

Malaysia

|

|

187.188.xxx.xxx

|

Iusacell PCS

|

Mexico

|

|

201.122.xxx.xxx

|

UniNet

|

Mexico

|

|

164.138.xxx.xxx

|

Tilaa

|

Netherlands

|

|

164.138.28.2

|

Tilaa

|

Netherlands

|

|

78.100.57.165

|

Qtel – Government Relations

|

Qatar

|

|

195.178.xxx.xxx

|

Tri.d.o.o / Telekom Srbija

|

Serbia

|

|

117.121.xxx.xxx

|

GPLHost

|

Singapore

|

|

217.174.229.82

|

Ministry of Communications

|

Turkmenistan

|

|

72.22.xxx.xxx

|

iPower, Inc.

|

United States

|

|

166.143.xxx.xxx

|

Verizon Wireless

|

United States

|

|

117.121.xxx.xxx

|

GPLHost

|

United States

|

|

117.121.xxx.xxx

|

GPLHost

|

United States

|

|

117.121.xxx.xxx

|

GPLHost

|

United States

|

|

117.121.xxx.xxx

|

GPLHost

|

United States

|

|

183.91.xxx.xxx

|

CMC Telecom Infrastructure Company

|

Vietnam

|

Vài phát hiện đó

đặc biệt đáng chú ý:

- 8 máy chủ được nhà cung cấp dịch vụ GPLHost đặt chỗ tại các quốc gia khác nhau (Singapore, Malaysia, Úc, Mỹ). Tuy nhiên, chúng tôi đã quan sát thấy chỉ 6 trong số các máy chủ đó tích cực bất kỳ lúc nào, gợi ý rằng một số địa chỉ IP có thể đã thay đổi trong quá trình quét của chúng tôi.

- Một máy chủ được nhận diện tại Đức có đăng ký “Gamma International GmbH”, và người liên hệ được liệt kê là “Martin Muench”.

- Có một máy chủ FinSpy trong một dải IP được đăng ký tới “Verizon Wireless”. Verizon Wireless bán các dải địa chỉ IP cho các khách hàng doanh nghiệp, nên điều này không nhất thiết là một chỉ số rằng bản thân Verizon Wireless đang vận hành máy chủ đó, hoặc rằng các khách hàng của Verizon Wireless đang bị gián điệp theo dõi.

- Một máy chủ tại Qatar từng bị Rapid7 dò ra trước đó dường như đã được đưa quay lại trực tuyến sau khi không hoạt động trong quá trình vòng quét cuối cùng của chúng tôi. Máy chủ đó được định vị trong dải 16 địa chỉ được đăng ký cho “Qtel – Corporate accounts – Government Relations”. Khối y hệt 16 địa chỉ cũng có website http://qhotels.gov.qa/.

3. Ethiopia và Việt

Nam: Thảo luận sâu các mẫu mới

3.1 FinSpy tại Ethiopia

Chúng tôi đã phân

tích một mẫu phần mềm độc hại có được gần đây

và đã xác định nó là FinSpy. Phần mềm độc hại đó

sử dụng các ảnh của các thành viên của nhóm đối lập

người Ethiopia. Ginbot 7, như là manh mối. Phần mềm độc

hại đó giao tiếp với một máy chủ chỉ huy & kiểm

soát FinSpy tại Ethiopia, nó từng được nhận diện lần

đầu bởi Rapid7 vào tháng 08/2012. Máy chủ đó từng được

dò tìm ra trong từng vòng quét, và vẫn hoạt động vào

thời điểm viết bài này. Nó có thể được thấy trong

khối địa chỉ sau, được Ethio Telecom, nhà cung cấp viễn

thông nhà nước Ethiopia quản lý.

|

IP: 213.55.99.74

route: 213.55.99.0/24 descr: Ethio Telecom origin: AS24757 mnt-by: ETC-MNT member-of: rs-ethiotelecom source: RIPE # Filtered |

Máy chủ dường như

được cập nhật theo một cách thức nhất quán với các

máy chủ khác, bao gồm các máy chủ tại Bahrain và

Turkmenistan.

|

MD5

|

8ae2febe04102450fdbc26a38037c82b

|

|

SHA-1

|

1fd0a268086f8d13c6a3262d41cce13470886b09

|

|

SHA-256

|

ff6f0bcdb02a9a1c10da14a0844ed6ec6a68c13c04b4c122afc559d606762fa

|

Mẫu đó là tương tự

như một mẫu

được phân tích trước đó của phần mềm độc hại

FinSpy được gửi cho các nhà hoạt động xã hội tại

Bahrain trong năm 2012. Hệt như các mẫu ở Bahrain, các phần

mềm độc hại tự tái định vị và bỏ một ảnh JPG

với cùng tên như là mẫu khi được một người sử dụng

không nghi ngờ thực thi. Điều này dường như là một ý

định lừa nạn nhân tin tưởng tệp được mở không

phải là độc hại. Đây là một ít những sự tương tự

chính giữa các mẫu:

- PE dấu thời gian “2011-07-05 08:25:31” gói là chính xác y hệt như mẫu của Bahrain.

- Chuỗi sau (được thấy trong một qui trình bị lây nhiễm với phần mềm độc hại), tự nhận diện phần mềm độc hại và tương tự như những chuỗi được thấy trong các mẫu của Barain:

(Xem

hình bên dưới, phần tiếng Anh)

- Các mẫu chia sẻ cùng Bootkit, SHA-256: ba21e452ee5ff3478f21b293a134b30ebf6b7f4ec03f8c8153202a740d7978b2.

- Các mẫu chia sẻ cùng tệp hệ thống driverw.sys, SHA-256: 62bde3bac3782d36f9f2e56db097a4672e70463e11971fad5de060b191efb196.

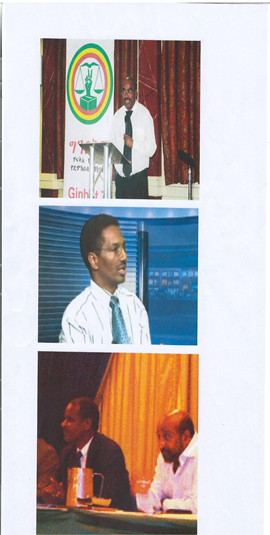

Hình 2. Ảnh

chỉ ra nạn nhân có các hình ảnh các thành viên của

Ginbot 7 - nhóm đối lập Ethiopia (Xem ảnh ở phần tiếng

Anh bên dưới)

Trong trường hợp này

ảnh có các hình chụp các thành viên của nhóm đối lập

người Ethiopia. Ginbot

7. Ngược lại, Ginbot 7 đã được chính phủ Ethiopia

chỉ định là một nhóm khủng bố vào năm 2001. Ủy ban

Bảo vệ các Nhà báo (CPJ) và Theo dõi Quyền Con người

(Human Rights Watch) cả 2 đều đã

chỉ trích hành động này. CPJ đã chỉ ra rằng đang

có một hiệu ứng làm nhụt nhuệ khí trong báo cáo chính

trị hợp pháp về nhóm và lãnh đạo của nó.

Sự tồn tại của

một mẫu FinSpy có hình ảnh đặc thù Ethiopia, và nó giao

tiếp với một máy chủ chỉ huy và kiểm soát vẫn còn

tích cực tại Ethiopia gợi ý mạnh mẽ rằng chính phủ

Ethiopia đang sử dụng FinSpy.

3.2 FinSpy Mobile tại

Việt Nam

Chúng

tôi gần đây đã có được và phân tích được một mẫu

phần mềm độc hại6 và đã nhận diện được

nó như là FinSpy Mobile cho Android. Mẫu này giao tiếp với

một máy chủ chỉ huy & kiểm soát ở Việt Nam, và

trích lọc các thông điệp văn bản đối với một số

điện thoại của Việt Nam.

Bộ

FinFisher bao gồm các phiên bản điện thoại di động của

FinSpy cho tất cả các nền tảng chính bao gồm iOS,

Android, Windows Mobile, Symbian và Blackberry. Các tính năng của

nó tương tự một cách rộng rãi với phiên bản cho máy

tính cá nhân PC của FinSpy được nhận diện ở Bahrain,

nhưng nó cũng có chứa các tính năng đặc thù di động

như theo dõi GPS và tính nawnng cho việc âm thâm 'gián điệp'

các cuộc gọi để ăn cắp trong các cuộc trao đổi gần

điện thoại. Một phân tích sâu bộ FinSpy Mobile các

cửa hậu đã được đưa ra trong một bài viết trên blog

gần đây: Điện

thoại thông minh - Ai đã yêu tôi: FinFisher đi Di động?

|

MD5

|

573ef0b7ff1dab2c3f785ee46c51a54f

|

|

SHA-1

|

d58d4f6ad3235610bafba677b762f3872b0f67cb

|

|

SHA-256

|

363172a2f2b228c7b00b614178e4ffa00a3a124200ceef4e6d7edb25a4696345

|

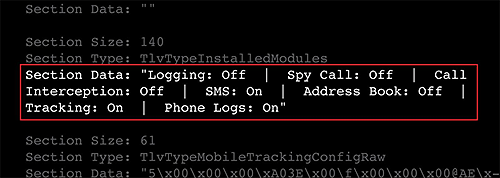

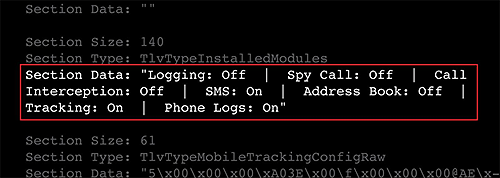

Mẫu

đã có một tệp cấu hình7 nó chỉ ra chức năng

có sẵn, và các lựa chọn từng được các chức năng đó

cho phép triển khai:

Hình

3: Ảnh của một phần tệp cấu hình cho mẫu FinSpy Mobile

(Xem ảnh ở phần tiếng Anh bên dưới)

Thú vị, tệp cấu

hình cũng chỉ định một số điện thoại Việt Nam được

sử dụng cho máy chủ chỉ huy và kiểm soát dựa vào SMS:

|

Section Type: TlvTypeConfigSMSPhoneNumber

Section Data: “+841257725403″ |

Máy chủ chỉ huy và

kiểm soát là trong một dãy được Công ty Hạ tầng Viễn

thông CMC tại Hà Nội cung cấp:

|

IP Address: 183.91.2.199

inetnum: 183.91.0.0 – 183.91.9.255 netname: FTTX-NET country: Vietnam address: CMC Telecom Infrastructure Company address: Tang 3, 16 Lieu Giai str, Ba Dinh, Ha Noi |

Máy

chủ này từng tích cực cho tới rất gần đây và đã

khớp với các chữ ký của chúng tôi cho một máy chủ

chỉ huy & kiểm soát FinSpy. Cả IP của máy chủ chỉ

huy & kiểm soát và số điện thoại được sử dụng

cho sự trích các thông điệp văn bản là tại Việt Nam

mà chỉ ra một chiến dịch trong nước.

Hình

như sự triển khai FinSpy này tại Việt Nam đang gây lo

lắng trong ngữ cảnh của những mối đe dọa gần đây

chống lại tự do ngôn luận và hoạt động xã hội trực

tuyến. Vào năm 2012, Việt Nam đã đưa ra các luật kiểm

duyệt mới trong một chiến dịch làm phiền, hăm dọa và

cầm giữ đang diễn ra chống lại các blogger mà nói chống

lại chế độ. Điều này đã lên tới cực điểm trong

vụ kiện 17 blogger, 14 trong số đó gần đây đã bị kết

tội và bị phạt từ từ 3 đến 13 năm8.

4.

Thảo luận ngắn về những phát hiện

Các

công ty bán phần mềm giám sát và thâm nhập thường kêu

rằng các công cụ của họ chỉ được sử dụng để

theo dõi các tội phạm và bọn khủng bố. FinFisher, VUPEN

và Hacking Team tất cả đã sử dụng lối nói tương tự9.

Vâng một loạt bằng chứng đang gia tưng gợi ý rằng các

công cụ đó đang thương xuyên được các quốc gia nơi

mà hoạt động chính trị không chính thống và phát ngôn

được tội phạm hóa. Những phát hiện của chúng tôi

nhấn mạnh sự nghịch nhĩ đang gia tăng giữa những kêu

ca công khai của Gamma rằng FinSpy được sử dụng hoàn

toàn để theo dõi “những kẻ xấu” và một loạt các

bằng chứng gợi ý rằng công cụ đó có và tiếp tục

được sử dụng để chống lại các nhóm đối lập và

các nhà hoạt động về quyền con người.

Trong

khi công việc của chúng tôi nhấn mạnh vào những nhánh

quyền con người về sự sử dụng sai công nghệ này,

điều rõ ràng là có những mối lo ngại rộng lớn hơn.

Một thị trường toàn cầu và không được điều chỉnh

đối với các công cụ tấn công số tiềm tàng hiện

diện một rủi ro mới cho cả an ninh không gian mạng quốc

gia và các công ty. Vào ngày 12/03, Giám đốc Tình báo Quốc

gia Mỹ James Clapper đã

nói trong báo cáo quốc hội đầu năm của ông về các

mối đe dọa an ninh:

“...

các công ty phát triển và bán các công nghệ chất lượng

chuyên nghiệp để hỗ trợ các hoạt động không gian

mạng - thường gắn thương hiệu cho các công cụ đó như

là các sản phẩm nghiên cứu an ninh phòng thủ hoặc can

thiệp hợp pháp. Các chính phủ nước ngoài sử dụng rồi

một số công cụ đó để nhằm vào các hệ thống của

Mỹ”.

Sự nở rộ toàn cầu

không được kiểm tra các sản phẩm như FinFisher là

trường hợp mạnh mẽ cho tranh luận chính sách về phần

mềm giám sát và sự thương mại hóa các khả năng tấn

công không gian mạng.

Những phát hiện mới

nhất của chúng tôi đưa ra một cái nhìn được cập

nhất về sự nở rộ toàn cầu của FinSpy. Chúng tôi đã

xác định được 36 máy chủ chỉ huy & kiểm soát

FinSpy tích cực, bao gồm 30 máy chủ còn chưa được biết

trước đó. Danh sách của chúng tôi về các máy chủ có

khả năng là không đầy đủ, khi một số máy chủ FinSpy

triển khai các biện pháp đối phó để ngăn chặn sự dò

tìm ra. Bao gồm các máy chủ được phát hiện vào năm

ngoái, chúng tôi bây giờ tính được các máy chủ FinSpy

ở 25 quốc gia, bao gồm các quốc gia với các hồ sơ đáng

lo ngại về các quyền con người. Điều này là biểu thị

một xu hướng toàn cầu hướng tới sự mua sắm các khả

năng tấn công không gian mạng của các chế độ không

dân chủ từ các công ty thương mại phương Tây.

Các mẫu FinSpy tại

Việt Nam và Ethiopia mà chúng tôi đã nhận diện được

sự điều tra đảm bảo xa hơn, đặc biệt đưa ra những

hồ sơ tồi về quyền con người của các nước đó.

Thực tế là phiên bản FinSpy của Ethiopia sử dụng các

hình ảnh của các thành viên đối lập như là manh mối

gợi ý nó có thể được sử dụng cho các hoạt động

giám sát có ảnh hưởng chính trị, hơn là các mục đích

ép tuân thủ luật một cách nghiệm ngặt.

Mẫu của Ethiopia là

mẫu FinSpy thứ 2 mà chúng tôi đã phát hiện có giao tiếp

với một máy chủ chúng tôi đã nhận diện bằng việc

quét như một máy chủ FinSpy chỉ huy & kiểm soát. Điều

này làm cho các kết quả quét của chúng tôi có hiệu

lực, và làm dấy lên câu hỏi đối với tuyên bố của

Gamma rằng những máy chủ như vậy “không … từ dòng

sản phẩm FinFisher”10. Những tương tự giữa

mẫu Ethiopia và những mẫu được sử dụng để nhằm

vào các nhà hoạt động xã hội của Bahrain cũng đưa ra

câu hỏi cho những tuyên bố trước đây của Gamma

International rằng các mẫu Bahrain từng là các bản sao

demo bị ăn cắp.

Trong

khi việc bán các phần mềm giám sát và thâm nhập như

vậy phần lớn chưa được điều chỉnh đúng mức, thì

vấn đề đã đưa ra sự soi xét mức cao đã gia tăng. Vào

tháng 9 nằm ngoái, bộ trưởng ngoại giao Đức, Guido

Westerwelle, đã kêu gọi một lệnh cấm rộng khắp EU về

xuất khẩu các phần mềm giám sát như vậy đối với

các quốc gia chuyên chế11. Trong cuộc phỏng vấn

vào tháng 12/2012, nghị sỹ quốc hội châu Âu (MEP)

Marietje Schaake, hiện là người chịu trách nhiệm báo cáo

cho chiến lược đầu tiên của EU về sự tự do số

trong chính sách đối ngoại, đã nói rằng từng “hoàn

toàn sốc” rằng các công ty của châu Âu tiếp tục xuất

khẩu các công nghệ đàn áp tới các nước nơi mà qui

định của luật còn gây tranh cãi12.

Chúng tôi thúc giục

các nhóm xã hội dân sự và các nhà báo đi theo các phát

hiện của chúng tôi tại các nước bị ảnh hưởng.

Chúng tôi cũng hy vọng rằng những phát hiện của chúng

tôi sẽ đưa ra thông tin có giá trị cho tranh luận chính

sách và công nghệ hiện hành về phần mềm giám sát và

sự thương mại hóa các khả năng tấn công không gian

mạng.

Các hiệu chỉnh

(15/03/2013)

* Bảng các địa chỉ

IP máy chủ FinFisher đã được rà soát lại so với xuất

bản ban đầu. Vì một vấn đề trong quá trình định

dạng, Ethio Telecom từng được xác định không đúng như

lf tại Estonia chứ không phải tại Ethiopia và Iusacell PCS

từng được xác định không đúng như là tại Malaysia

chứ không phải ở Mexico. Dãy IP 117.121.xxx.xxx tương ứng

với GPLHost, nằm ở Malaysia. Iusacell PCS tương ứng với

187.188.xxx.xxx và nằm ở Mexico.

Thừa nhận

Chúng tôi muốn cảm

ơn Eva Galperin và Quỹ Điện tử Phi biên giới - EFF

(Electronic Frontier Foundation), Privacy International, Bahrain

Watch, and Drew Hintz.

Tham khảo các phương

tiện truyền thông

Tham

khảo các phương tiện truyền thông về báo cáo này gồm

HuffingtonPost

Canada, Salon,

The

Verge, Bloomberg

Business Week, TheYoungTurks.

(Xem

phần chú giải cuối trang ở cuối cùng của bài, sau phần

tiếng Anh).

Authors:

Morgan Marquis-Boire, Bill Marczak, Claudio Guarnieri, and John

Scott-Railton.

This

post describes the results of a comprehensive global Internet scan

for the command and control servers of FinFisher’s surveillance

software. It also details the discovery of a campaign using FinFisher

in Ethiopia used to target individuals linked to an opposition group.

Additionally, it provides examination of a FinSpy Mobile sample found

in the wild, which appears to have been used in Vietnam.

Summary

of Key Findings

- We have found command and control servers for FinSpy backdoors, part of Gamma International’s FinFisher “remote monitoring solution,” in a total of 25 countries: Australia, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Brunei, Canada, Czech Republic, Estonia, Ethiopia, Germany, India, Indonesia, Japan, Latvia, Malaysia, Mexico, Mongolia, Netherlands, Qatar, Serbia, Singapore, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, United States, Vietnam.

- A FinSpy campaign in Ethiopia uses pictures of Ginbot 7, an Ethiopian opposition group, as bait to infect users. This continues the theme of FinSpy deployments with strong indications of politically-motivated targeting.

- There is strong evidence of a Vietnamese FinSpy Mobile Campaign. We found an Android FinSpy Mobile sample in the wild with a command & control server in Vietnam that also exfiltrates text messages to a local phone number.

- These findings call into question claims by Gamma International that previously reported servers were not part of their product line, and that previously discovered copies of their software were either stolen or demo copies.

1.

Background and Introduction

FinFisher

is a line of remote intrusion and surveillance software developed by

Munich-based Gamma International GmbH. FinFisher products are

marketed and sold exclusively to law enforcement and intelligence

agencies by the UK-based Gamma Group.1

Although touted as a “lawful interception” suite for monitoring

criminals, FinFisher has gained notoriety because it has been used in

targeted attacks against human rights campaigners and opposition

activists in countries with questionable human rights records.2

In

late July 2012, we published

the results of an investigation into a suspicious e-mail campaign

targeting Bahraini activists.3

We analyzed the attachments and discovered that they contained the

FinSpy spyware, FinFisher’s remote monitoring product. FinSpy

captures information from an infected computer, such as passwords and

Skype calls, and sends the information to a FinSpy command &

control (C2) server. The attachments we analyzed sent data to a

command & control server inside Bahrain.

This

discovery motivated researchers to search for other command &

control servers to understand how widely FinFisher might be used.

Claudio Guarnieri at Rapid7 (one of the authors of this report) was

the first to search for these servers. He fingerprinted the Bahrain

server and looked at historical Internet

scanning data to identify other servers around the world that

responded to the same fingerprint. Rapid7 published this list of

servers, and described their fingerprinting technique. Other groups,

including CrowdStrike

and SpiderLabs

also analyzed and published reports on FinSpy.

Immediately

after publication, the servers were apparently updated to evade

detection by the Rapid7 fingerprint. We devised a different

fingerprinting technique and scanned portions of the internet. We

confirmed Rapid7’s results, and also found several new servers,

including one inside Turkmenistan’s Ministry of Communications. We

published our list of servers in late August 2012, in addition to an

analysis of mobile phone versions of FinSpy. FinSpy servers were

apparently updated again in October 2012 to disable this newer

fingerprinting technique, although it was never publicly described.

Nevertheless,

via analysis of existing samples and observation of command &

control servers, we managed to enumerate yet more fingerprinting

methods and continue our survey of the internet for this surveillance

software. We describe the results in this post.

Civil

society groups have found cause for concern in these findings, as

they indicate the use of FinFisher products by countries like

Turkmenistan and Bahrain with problematic records on human rights,

transparency, and rule of law. In an August 2012 response to a letter

from UK-based NGO Privacy International, the UK Government revealed

that at some unspecified time in the past, it had examined a version

of FinSpy, and communicated to Gamma that a license would be required

to export that version outside of the EU. Gamma has repeatedly denied

links to spyware and servers uncovered by our research, claiming that

the servers detected by our scans are “not

… from the FinFisher product line.”4

Gamma also claims that the spyware sent to activists in Bahrain was

an “old” demonstration version of FinSpy, stolen during a product

presentation.

In

February 2013, Privacy International, the European Centre for

Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), the Bahrain Center for Human

Rights, Bahrain Watch, and Reporters Without Borders filed

a complaint with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development (OECD), requesting that this body investigate whether

Gamma violated OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises by

exporting FinSpy to Bahrain. The complaint called previous Gamma

statements into question, noting that at least two different versions

(4.00 and 4.01) of FinSpy were found in Bahrain, and that Bahrain’s

server was a FinFisher product and was likely receiving updates from

Gamma. This complaint, as

laid out by Privacy International states that Gamma:

- failed to respect the internationally recognised human rights of those affected by [its] activities

- caused and contributed to adverse human rights impacts in the course of [its] business activities

- failed to prevent and mitigate adverse human rights impacts linked to [its] activities and products, and failed to address such impacts where they have occurred

- failed to carry out adequate due diligence (including human rights due diligence); and

- failed to implement a policy commitment to respect human rights.

According to recent

reporting, German Federal Police appear to have plans to purchase

and use the FinFisher suite of tools domestically within Germany.5

Meanwhile, findings by our group and others continue to illustrate

the global proliferation of FinFisher’s products. Research

continues to uncover troubling cases of FinSpy in countries with

dismal human rights track records, and politically repressive

regimes. Most recently, work by Bahrain

Watch has confirmed the presence of a Bahraini FinFisher

campaign, and further contradicted Gamma’s public statements. This

post adds to the list by providing an updated list of FinSpy Command

& Control servers, and describing the FinSpy malware samples in

the wild which appear to have been used to target victims in Ethiopia

and Vietnam.

We

present these updated findings in the hopes that we will further

encourage civil society groups and competent investigative bodies to

continue their scrutiny of Gamma’s activities, relevant export

control issues, and the issue of the global and unregulated

proliferation of surveillance malware.

2.

FinFisher: Updated Global Scan

(click image to

enlarge)

Figure 1. Map of global FinFisher proliferation

Figure 1. Map of global FinFisher proliferation

Around

October 2012, we observed that the behavior of FinSpy servers began

to change. Servers stopped responding to our fingerprint, which had

exploited a quirk in the distinctive FinSpy wire protocol. We believe

that this indicates that Gamma either independently changed the

FinSpy protocol, or was able to determine key elements of our

fingerprint, although it has never been publicly revealed.

In

the wake of this apparent update to FinSpy command & control

servers, we devised a new fingerprint and conducted a scan of the

internet for FinSpy command & control servers. This scan took

roughly two months and involved sending more than 12 billion packets.

Our new scan identified a total of 36 FinSpy servers, 30 of which

were new and 6 of which we had found during previous scanning. The

servers operated in 19 different countries. Among the FinSpy servers

we found, 7 were in countries we hadn’t seen before.

New

Countries

Canada,

Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, Mexico, Serbia, Vietnam

In

our most recent scan, 16 servers that we had previously found did not

show up. We suspect that after our earlier scans were published the

operators moved them. Many of these servers were shut down or

relocated after the publication of previous results, but before the

apparent October 2012 update. We no longer found FinSpy servers in 4

countries where previous scanning identified them (Brunei, UAE,

Latvia, and Mongolia). Taken together, FinSpy servers are currently,

or have been present, in 25 countries.

Australia,

Bahrain, Bangladesh, Brunei, Canada, Czech Republic, Estonia,

Ethiopia, Germany, India, Indonesia, Japan, Latvia, Malaysia, Mexico,

Mongolia, Netherlands, Qatar, Serbia, Singapore, Turkmenistan, United

Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, United States, Vietnam.

Importantly,

we believe that our list of servers is incomplete due to the large

diversity of ports used by FinSpy servers, as well as other efforts

at concealment. Moreover, discovery of a FinSpy command and control

server in a given country is not a sufficient indicator to conclude

the use of FinFisher by that country’s law enforcement or

intelligence agencies. In some cases, servers were found running on

facilities provided by commercial hosting providers that could have

been purchased by actors from any country.

The

table below shows the FinSpy servers detected in our latest scan. We

list the full IP address of servers that have been previously

publicly revealed. For active servers that have not been publicly

revealed, we list the first two octets only. Releasing complete IP

addresses in the past has not proved useful, as the servers are

quickly shut down and relocated.*

|

IP

|

Operator

|

Routed to

Country

|

|

117.121.xxx.xxx

|

GPLHost

|

Australia

|

|

77.69.181.162

|

Batelco ADSL

Service

|

Bahrain

|

|

180.211.xxx.xxx

|

Telegraph &

Telephone Board

|

Bangladesh

|

|

168.144.xxx.xxx

|

Softcom, Inc.

|

Canada

|

|

168.144.xxx.xxx

|

Softcom, Inc.

|

Canada

|

|

217.16.xxx.xxx

|

PIPNI VPS

|

Czech Republic

|

|

217.146.xxx.xxx

|

Zone Media

UVS/Nodes

|

Estonia

|

|

213.55.99.74

|

Ethio Telecom

|

Ethiopia

|

|

80.156.xxx.xxx

|

Gamma

International GmbH

|

Germany

|

|

37.200.xxx.xxx

|

JiffyBox

Servers

|

Germany

|

|

178.77.xxx.xxx

|

HostEurope GmbH

|

Germany

|

|

119.18.xxx.xxx

|

HostGator

|

India

|

|

119.18.xxx.xxx

|

HostGator

|

India

|

|

118.97.xxx.xxx

|

PT Telkom

|

Indonesia

|

|

118.97.xxx.xxx

|

PT Telkom

|

Indonesia

|

|

103.28.xxx.xxx

|

PT Matrixnet

Global

|

Indonesia

|

|

112.78.143.34

|

Biznet ISP

|

Indonesia

|

|

112.78.143.26

|

Biznet ISP

|

Indonesia

|

|

117.121.xxx.xxx

|

GPLHost

|

Malaysia

|

|

187.188.xxx.xxx

|

Iusacell PCS

|

Mexico

|

|

201.122.xxx.xxx

|

UniNet

|

Mexico

|

|

164.138.xxx.xxx

|

Tilaa

|

Netherlands

|

|

164.138.28.2

|

Tilaa

|

Netherlands

|

|

78.100.57.165

|

Qtel –

Government Relations

|

Qatar

|

|

195.178.xxx.xxx

|

Tri.d.o.o /

Telekom Srbija

|

Serbia

|

|

117.121.xxx.xxx

|

GPLHost

|

Singapore

|

|

217.174.229.82

|

Ministry of

Communications

|

Turkmenistan

|

|

72.22.xxx.xxx

|

iPower, Inc.

|

United States

|

|

166.143.xxx.xxx

|

Verizon

Wireless

|

United States

|

|

117.121.xxx.xxx

|

GPLHost

|

United States

|

|

117.121.xxx.xxx

|

GPLHost

|

United States

|

|

117.121.xxx.xxx

|

GPLHost

|

United States

|

|

117.121.xxx.xxx

|

GPLHost

|

United States

|

|

183.91.xxx.xxx

|

CMC Telecom

Infrastructure Company

|

Vietnam

|

Several

of these findings are especially noteworthy:

- Eight servers are hosted by provider GPLHost in various countries (Singapore, Malaysia, Australia, US). However, we observed only six of these servers active at any given time, suggesting that some IP addresses may have changed during our scans.

- A server identified in Germany has the registrant “Gamma International GmbH,” and the contact person is listed as “Martin Muench.”

- There is a FinSpy server in an IP range registered to “Verizon Wireless.” Verizon Wireless sells ranges of IP addresses to corporate customers, so this is not necessarily an indication that Verizon Wireless itself is operating the server, or that Verizon Wireless customers are being spied on.

- A server in Qatar that was previously detected by Rapid7 seems to be back online after being unresponsive during the last round of our scanning. The server is located in a range of 16 addresses registered to “Qtel – Corporate accounts – Government Relations.” The same block of 16 addresses also contains the website http://qhotels.gov.qa/.

3.

Ethiopia and Vietnam: In-depth Discussion of New Samples

3.1

FinSpy in Ethiopia

We

analyzed a recently acquired malware sample and identified it as

FinSpy. The malware uses images of members of the Ethiopian

opposition group, Ginbot 7, as bait. The malware

communicates with a FinSpy Command & Control server in Ethiopia,

which was first identified by Rapid7 in August 2012. The server has

been detected in every round of scanning, and remains operational at

the time of this writing. It can be found in the following address

block run by Ethio Telecom, Ethiopia’s state-owned

telecommunications provider:

|

IP:

213.55.99.74

route: 213.55.99.0/24 descr: Ethio Telecom origin: AS24757 mnt-by: ETC-MNT member-of: rs-ethiotelecom source: RIPE # Filtered |

The

server appears to be updated in a manner consistent with other

servers, including servers in Bahrain and Turkmenistan.

|

MD5

|

8ae2febe04102450fdbc26a38037c82b

|

|

SHA-1

|

1fd0a268086f8d13c6a3262d41cce13470886b09

|

|

SHA-256

|

ff6f0bcdb02a9a1c10da14a0844ed6ec6a68c13c04b4c122afc559d606762fa

|

The

sample is similar to a

previously analyzed sample of FinSpy malware sent to activists in

Bahrain in 2012. Just like Bahraini samples, the malware relocates

itself and drops a JPG image with the same filename as the sample

when executed by an unsuspecting user. This appears to be an attempt

to trick the victim into believing the opened file is not malicious.

Here are a few key similarities between the samples:

- The PE timestamp “2011-07-05 08:25:31” of the packer is exactly the same as the Bahraini sample.

- The following string (found in a process infected with the malware), self-identifies the malware and is similar to strings found in the Bahraini samples:

- The samples share the same Bootkit, SHA-256: ba21e452ee5ff3478f21b293a134b30ebf6b7f4ec03f8c8153202a740d7978b2.

- The samples share the same driverw.sys file, SHA-256: 62bde3bac3782d36f9f2e56db097a4672e70463e11971fad5de060b191efb196.

Figure 2. The image shown to the victim contains pictures of members of the Ginbot 7 Ethiopian opposition group

In

this case the picture contains photos of members of the

Ethiopian opposition group, Ginbot

7. Controversially, Ginbot 7 was designated a terrorist group by

the Ethiopian Government in 2011. The Committee to Protect

Journalists (CPJ) and Human Rights Watch have both criticized

this action,

CPJ has pointed out that it is having a chilling effect on legitimate

political reporting about the group and its leadership.

The

existence of a FinSpy sample that contains Ethiopia-specific imagery,

and that communicates with a still-active command & control

server in Ethiopia strongly suggests that the Ethiopian Government is

using FinSpy.

3.2

FinSpy Mobile in Vietnam

We

recently obtained and analyzed a malware sample6

and identified it as FinSpy Mobile for Android. The sample

communicates with a command & control server in Vietnam, and

exfiltrates text messages to a Vietnamese telephone number.

The

FinFisher suite includes mobile phone versions of FinSpy for all

major platforms including iOS, Android, Windows Mobile, Symbian and

Blackberry. Its features are broadly similar to the PC version of

FinSpy identified in Bahrain, but it also contains mobile-specific

features such as GPS tracking and functionality for silent ‘spy’

calls to snoop on conversations near the phone. An in-depth analysis

of the FinSpy Mobile suite of backdoors was provided in an earlier

blog post: The

Smartphone Who Loved Me: FinFisher Goes Mobile?

|

MD5

|

573ef0b7ff1dab2c3f785ee46c51a54f

|

|

SHA-1

|

d58d4f6ad3235610bafba677b762f3872b0f67cb

|

|

SHA-256

|

363172a2f2b228c7b00b614178e4ffa00a3a124200ceef4e6d7edb25a4696345

|

The

sample included a configuration file7

that indicates available functionality, and the options that have

been enabled by those deploying it:

Figure 3. Image of a section of a configuration file for the FinSpy Mobile sample

Figure 3. Image of a section of a configuration file for the FinSpy Mobile sample

Interestingly,

the configuration file also specifies a Vietnamese phone number used

for SMS based command and control:

|

Section Type:

TlvTypeConfigSMSPhoneNumber

Section Data: “+841257725403″ |

The

command and control server is in a range provided by the CMC Telecom

Infrastructure Company in Hanoi:

|

IP Address:

183.91.2.199

inetnum: 183.91.0.0 – 183.91.9.255 netname: FTTX-NET country: Vietnam address: CMC Telecom Infrastructure Company address: Tang 3, 16 Lieu Giai str, Ba Dinh, Ha Noi |

This

server was active until very recently and matched our signatures for

a FinSpy command and control server. Both the command & control

server IP and the phone number used for text-message exfiltration are

in Vietnam which indicates a domestic campaign.

This

apparent FinSpy deployment in Vietnam is troubling in the context of

recent threats against online free expression and activism. In 2012,

Vietnam introduced new censorship laws amidst an ongoing harassment,

intimidation, and detention campaign against of bloggers who spoke

out against the regime. This culminated in the trial of 17 bloggers,

14 of whom were recently convicted and sentenced to terms ranging

from 3 to 13 years.8

4.

Brief Discussion of Findings

Companies

selling surveillance and intrusion software commonly claim that their

tools are only used to track criminals and terrorists. FinFisher,

VUPEN and Hacking Team have all used similar language.9

Yet a growing body of evidence suggests that these tools are

regularly obtained by countries where dissenting political activity

and speech is criminalized. Our findings highlight the increasing

dissonance between Gamma’s public claims that FinSpy is used

exclusively to track “bad guys” and the growing body of evidence

suggesting that the tool has and continues to be used against

opposition groups and human rights activists.

While

our work highlights the human rights ramifications of the mis-use of

this technology, it is clear that there are broader concerns. A

global and unregulated market for offensive digital tools potentially

presents a novel risk to both national and corporate cyber-security.

On March 12th, US Director of National Intelligence James Clapper

stated

in his yearly congressional report on security threats:

“…companies

develop and sell professional-quality technologies to support

cyberoperations–often branding these tools as lawful-intercept or

defensive security research products. Foreign governments already use

some of these tools to target U.S. Systems.”

The

unchecked global proliferation of products like FinFisher makes a

strong case for policy debate about surveillance software and the

commercialization of offensive cyber-capabilities.

Our

latest findings give an updated look at the global proliferation of

FinSpy. We identified 36 active FinSpy command & control servers,

including 30 previously-unknown servers. Our list of servers is

likely incomplete, as some FinSpy servers employ countermeasures to

prevent detection. Including servers discovered last year, we now

count FinSpy servers in 25 countries, including countries with

troubling human rights records. This is indicative of a global trend

towards the acquisition of offensive cyber-capabilities by

non-democratic regimes from commercial Western companies.

The

Vietnamese and Ethiopian FinSpy samples we identified warrant further

investigation, especially given the poor human rights records of

these countries. The fact that the Ethiopian version of FinSpy uses

images of opposition members as bait suggests it may be used for

politically influenced surveillance activities, rather than strictly

law enforcement purposes.

The

Ethiopian sample is the second FinSpy sample we have discovered that

communicates with a server we identified by scanning as a FinSpy

command & control server. This further validates our scanning

results, and calls into question Gamma’s claim that such servers

are “not … from the

FinFisher product line.”10

Similarities between the Ethiopian sample and those used to target

Bahraini activists also bring into question Gamma International’s

earlier claims that the Bahrain samples were stolen demonstration

copies.

While

the sale of such intrusion and surveillance software is largely

unregulated, the issue has drawn increased high-level scrutiny. In

September of last year, the German foreign minister, Guido

Westerwelle, called for an EU-wide ban on the export of such

surveillance software to totalitarian states.11

In a December 2012 interview, Marietje Schaake (MEP), currently the

rapporteur for the first EU strategy on digital freedom in foreign

policy, stated that it was “quite shocking” that Europe companies

continue to export repressive technologies to countries where the

rule of law is in question.12

We

urge civil society groups and journalists to follow up on our

findings within affected countries. We also hope that our findings

will provide valuable information to the ongoing technology and

policy debate about surveillance software and the commercialisation

of offensive cyber-capabilities.

Corrections

(15 March 2013):

*

The table of FinFisher server IP addresses has been revised since the

original publication. Due to an issue during formatting, Ethio

Telecom was incorrectly identified as being in Estonia rather than in

Ethiopia and Iusacell PCS was incorrectly identified as being in

Malaysia rather than in Mexico. The IP range 117.121.xxx.xxx

corresponds with GPLHost, which is located in Malaysia.

Iusacell PCS corresponds with 187.188.xxx.xxx and is located in

Mexico.

Acknowledgements

We’d

like to thank Eva Galperin and the Electronic Frontier Foundation

(EFF), Privacy International, Bahrain Watch, and Drew Hintz.

Media

Coverage

Media

coverage of the report includes HuffingtonPost

Canada, Salon,

The

Verge, Bloomberg

Business Week, TheYoungTurks.

Footnotes

Lời chú cuối trang

1https://www.gammagroup.com/

2Software Meant to Fight Crime Is Used to Spy on Dissidents, http://goo.gl/GDRMe, New York Times, August 31, 2012, Page A1 Print edition.

3Cyber Attacks on Activists Traced to FinFisher Spyware of Gamma, http://goo.gl/nJH7o, Bloomberg, July 25, 2012

4http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/08/16/company-denies-role-in-recently-uncovered-spyware/

5http://www.sueddeutsche.de/digital/finfisher-entwickler-gamma-spam-vom-staat-1.1595253

6This sample has also been discussed by Denis Maslennikov from Kasperksy in his analyses of FinSpy Mobile – https://www.securelist.com/en/analysis/204792283/Mobile_Malware_Evolution_Part_6

7Configuration parsed with a tool written by Josh Grunzweig of Spider Labs – http://blog.spiderlabs.com/2012/09/finspy-mobile-configuration-and-insight.html

8https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2013/01/bloggers-trial-vietnam-are-part-ongoing-crackdown-free-expression

9https://www.securityweek.com/podcast-vupen-ceo-chaouki-bekrar-addresses-zero-day-marketplace-controversy-cansecwest

10http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/08/16/company-denies-role-in-recently-uncovered-spyware/

11http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2012/nov/28/offshore-company-directors-military-intelligence

12http://www.vieuws.eu/foreign-affairs/digital-freedoms-marietje-schaake-mep-alde/

2Software Meant to Fight Crime Is Used to Spy on Dissidents, http://goo.gl/GDRMe, New York Times, August 31, 2012, Page A1 Print edition.

3Cyber Attacks on Activists Traced to FinFisher Spyware of Gamma, http://goo.gl/nJH7o, Bloomberg, July 25, 2012

4http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/08/16/company-denies-role-in-recently-uncovered-spyware/

5http://www.sueddeutsche.de/digital/finfisher-entwickler-gamma-spam-vom-staat-1.1595253

6This sample has also been discussed by Denis Maslennikov from Kasperksy in his analyses of FinSpy Mobile – https://www.securelist.com/en/analysis/204792283/Mobile_Malware_Evolution_Part_6

7Configuration parsed with a tool written by Josh Grunzweig of Spider Labs – http://blog.spiderlabs.com/2012/09/finspy-mobile-configuration-and-insight.html

8https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2013/01/bloggers-trial-vietnam-are-part-ongoing-crackdown-free-expression

9https://www.securityweek.com/podcast-vupen-ceo-chaouki-bekrar-addresses-zero-day-marketplace-controversy-cansecwest

10http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/08/16/company-denies-role-in-recently-uncovered-spyware/

11http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2012/nov/28/offshore-company-directors-military-intelligence

12http://www.vieuws.eu/foreign-affairs/digital-freedoms-marietje-schaake-mep-alde/

Post written by Morgan

Marquis-Boire

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét

Lưu ý: Chỉ thành viên của blog này mới được đăng nhận xét.