Inside the Museum is Outside the Museum — Thoughts on Open Access and Organisational Culture

Karin Glasemann, Mar 13 · 18 min read

Theo: https://medium.com/open-glam/inside-the-museum-is-outside-the-museum-thoughts-on-open-access-and-organisational-culture-1e9780d6385b

Bài được đưa lên Internet ngày: 13/03/2020

Karin Glasemann, Mar 13 · 18 min read

Theo: https://medium.com/open-glam/inside-the-museum-is-outside-the-museum-thoughts-on-open-access-and-organisational-culture-1e9780d6385b

Bài được đưa lên Internet ngày: 13/03/2020

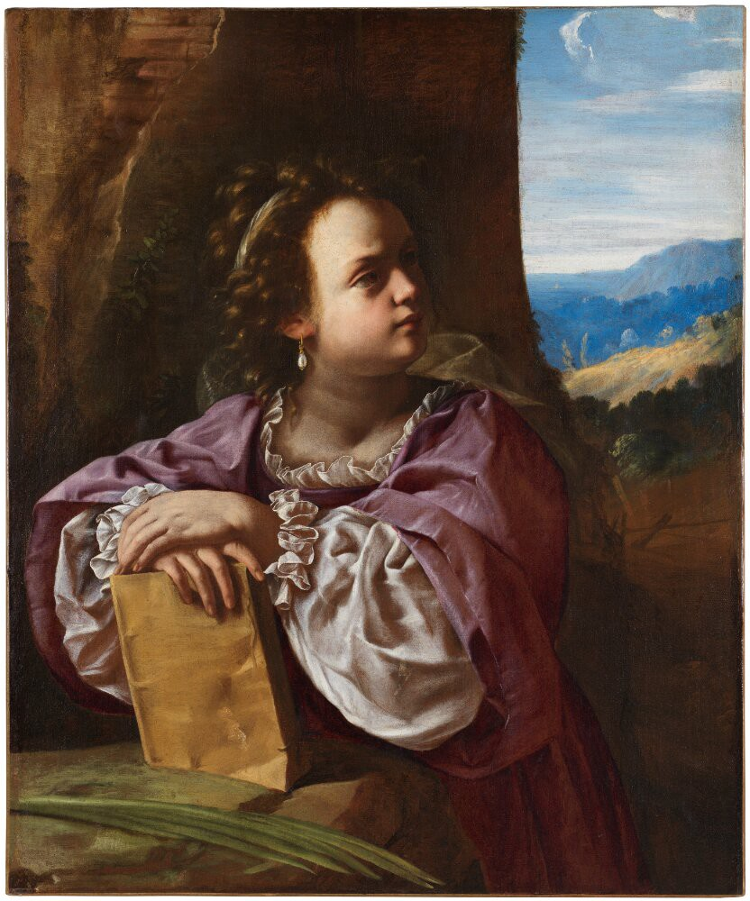

St. Catherine of Alexandria, của Artemisia Gentileschi. Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia, phạm vi công cộng

“Chỉ khi nào các cơ sở văn hóa bắt đầu sử dụng các công nghệ số để thúc đẩy các phương pháp nghiên cứu mới và làm việc cộng tác (…), khi đó họ thực sự đã bắt đầu nghĩ theo kỹ thuật số”. Giáo sư Ellen Euler.

Trích dẫn ở trên tóm tắt kinh nghiệm làm việc của tôi với số hóa và phát triển số

ở viện bảo tàng quốc gia, viện bảo tàng nghệ thuật và thiết kế Thụy

Điển, trong vòng 7 năm qua. Nhưng từ thường nói “nghĩ theo kỹ thuật số”

ngụ ý gì trong một tổ chức văn hóa và Truy cập Mở có liên quan gì tới

nó?

Vài năm qua, chúng tôi đã thấy sự dịch

chuyển dạng thức nơi các viện bảo tàng điều chỉnh sự giải thích các

tuyên bố sứ mệnh của họ hướng tới việc khuyến khích đối thoại và trao

quyền cho các khách viếng thăm để định hình các trải nghiệm văn hóa của

riêng họ. Một cách lý tưởng, vai trò của viện bảo tàng trong kịch bản

này dịch chuyển từ chủ yếu là cơ sở thu thập, giảng dạy và bảo tồn sang

vai trò uyển chuyển hơn trong cung cấp sự truy cập, xúc tác cho thảo

luận và trao đổi.

Sự biến đổi số rộng lớn hơn của xã hội

một phần đã khởi xướng, và đang nuôi dưỡng, sự biến đổi vai trò này của

viện bảo tàng. “Số hóa” hạ thấp các rào cản truy cập, cho phép tham gia

và thảo luận theo dạng thức dễ dàng hơn nhiều và, quan trọng nhất, nó

chào tiềm năng cho bất kỳ ai để xây dựng dựa vào các tài sản đó và mở

rộng tri thức mà viện bảo tàng chào.

Tuy nhiên, tiềm năng vốn dĩ này không ngụ

ý nó được sử dụng với mức độ đầy đủ của nó. Dù nhằm để trở thành một cơ

sở mở là nền tảng cho các mục tiêu của hầu hết các viện bảo tàng, sự

đồng thuận về “tính mở” đạt được tốt nhất như thế nào dường như còn xa

mới đạt được.

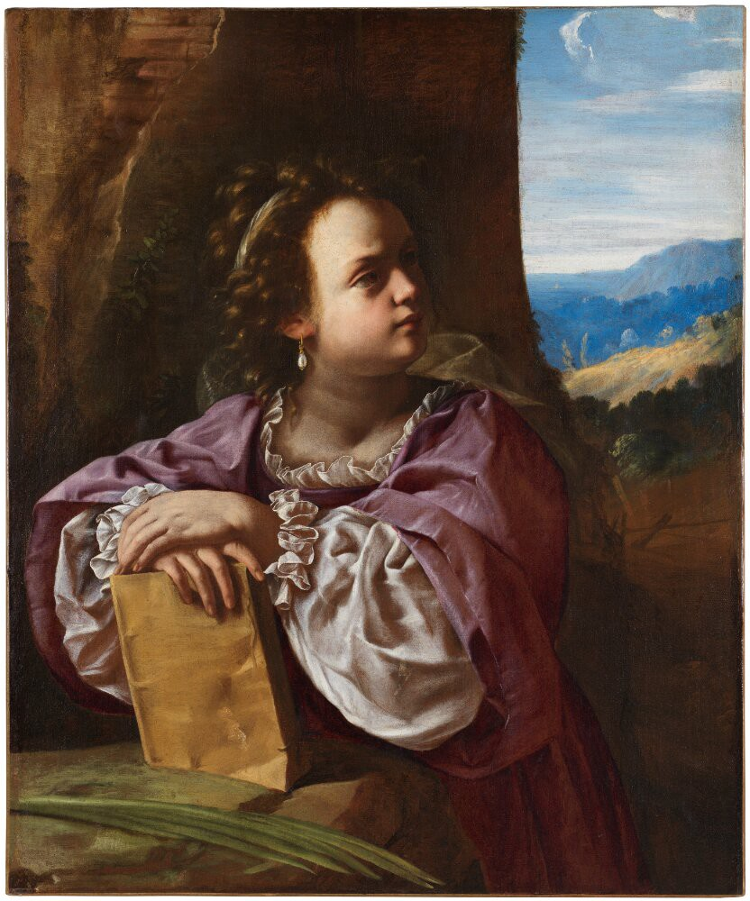

Cảnh hồ ở Engelsberg, Västmanland, của Olof Arborelius. Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia, phạm vi công cộng

Từ bỏ kiểm soát bằng OpenGLAM

Khái niệm theo đó các cơ sở cung cấp truy

cập tới các bộ sưu tập số của họ, ở vài mức độ, thể hiện thiện chí của

họ để nhường lại quyền kiểm soát xung quanh các câu chuyện được kể về

các bộ sưu tập đó. Các viện bảo tàng thiết kế các kinh nghiệm của người

sử dụng như thế nào xung quanh các bộ sưu tập số của họ? Họ khuyến khích

- hay không khuyến khích - sử dụng lại các tài sản số của họ như thế

nào?

Phong trào được biết tới như là Open GLAM xây dựng dựa vào cơ sở rằng dữ liệu di sản văn hóa nên được chia sẻ cởi mở, nghĩa là, ‘Dữ liệu và nội dung mở có thể được bất kỳ ai vì bất kỳ mục đích gì tự do không mất tiền để sử dụng, sửa đổi, và chia sẻ.

Nguyên tắc của tính mở đó từng là một phần của phát triển web từ lâu

trước khi nó với tới được lĩnh vực di sản văn hóa. Đặc biệt đối với các

viện bảo tàng nghệ thuật, OpenGLAM ngụ ý số hóa nên không bao giờ bổ

sung thêm bản quyền mới - và vì thế ngụ ý sự kiểm soát - đối với các tác

phẩm nghệ thuật văn hóa trong phạm vi công cộng.

Để cho phép sử dụng lại tự do không mất

tiền, các bộ sưu tập được số hóa dịch chuyển từ các triển lãm thụ động

sang trở thành tư liệu thô cho bất kỳ người sử dụng nào để hưởng thụ,

học tập từ đó và xây dựng dựa vào nó. Dù đã có sự kháng cự

chống lại phong trào OpenGLAM, số lượng ngày một tăng các cơ sở áp dụng

các chính sách mở được cho là chậm như có xung lượng không thể dừng

được hướng tới tính mở lớn hơn.

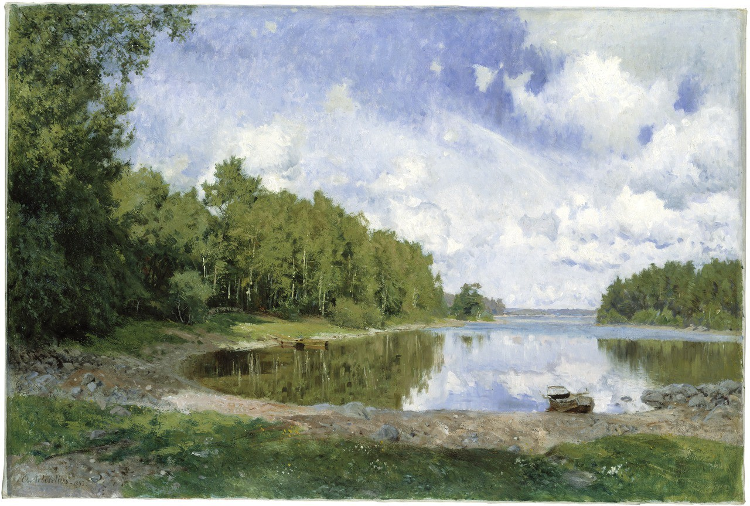

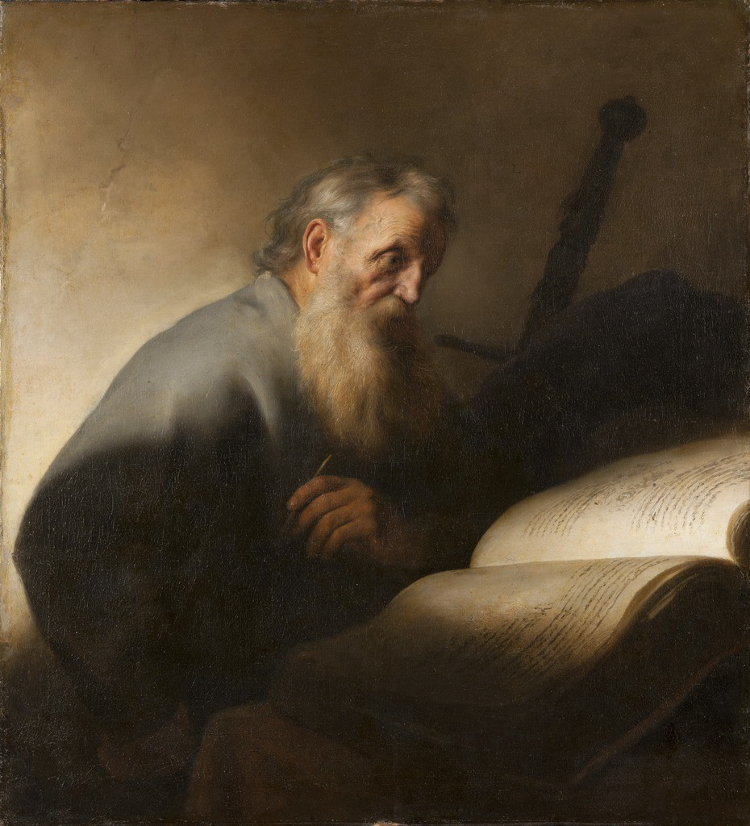

Apostle Paul của Jan Lievens. Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia, phạm vi công cộng

Những người gây ảnh hưởng của OpenGLAM và Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia

Phong trào OpenGLAM trong lĩnh vực bảo

tàng đã lan rộng khắp châu Âu rồi từ Rijksmuseum năm 2011, và vài cơ sở ở

Mỹ đã bước theo sau, với Viện Smithsonian như là mới nhất, hầu hết sự bổ sung có tính minh họa cho đám đông của OpenGLAM.

Từ 2012, tổ chức viện bảo tàng đầu tiên của Thụy Điển, cơ quan chính

phủ của Livrustkammaren och Skoklosters slott med Stiftelsen Hallwylska

Museet (LSH), đã quyết định mở kho lưu trữ ảnh của nó để sử dụng lại không giới hạn, trong cộng tác với Wikimedia Thụy Điển.

Phòng trưng bày Quốc gia Đan Mạch, SMK, từng strong có tiếng nói mạnh mẽ ủng hộ OpenGLAM kể từ ngay ban đầu. Nó đã làm cho bộ sưu tập của nó tải về được và sử dụng lại được ở phạm vi rộng vào năm 2015. Ngay sau đó, Viện bảo tàng für Kunst und Gewerbe

đã mở ra bộ sưu tập của nó cho sử dụng lại tự do không mất tiền, trở

thành viện bảo tàng nghệ thuật đầu tiên của Đức làm như vậy.

Các ví dụ đó đã giúp tăng tốc thảo luận hướng tới tính mở nhiều hơn ở Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia, dẫn tới tuyên bố chính sách OpenGLAM của nó vào tháng 10/2016 —

vài tháng trước khi Viện bảo tàng Nghệ thuật Thủ đô, như là một trong

những cơ sở mạnh trong lĩnh vực viện bảo tàng nghệ thuật, đã xuất bản sáng kiến Truy cập Mở của nó vào năm 2017.

Khi Giám đốc Số của Met, Loic Tallon, đã quyết định từ nhiệm vào tháng 3/2019,

Tổng Giám đốc của Met Mã Hollein đã ca ngợi công việc của ông bằng việc

lên khung cho “sáng kiến Truy cập Mở, theo đó Viện bảo tàng đã phát

hành hơn 400.000 hình ảnh các tác phẩm nghệ thuật trong bộ sưu tập để

bất kỳ cá nhân nào trên thế giới sử dụng không có giới hạn” như một

trong những di sản quan trọng nhất của ông. Sáng kiến Truy cập Mở,

Hollein nói, đã biến đổi cách Met kết nối với các khán thính phòng, và

đã được khuếch đại mạnh mẽ thông qua việc xây dựng các quan hệ đối tác

mạnh.

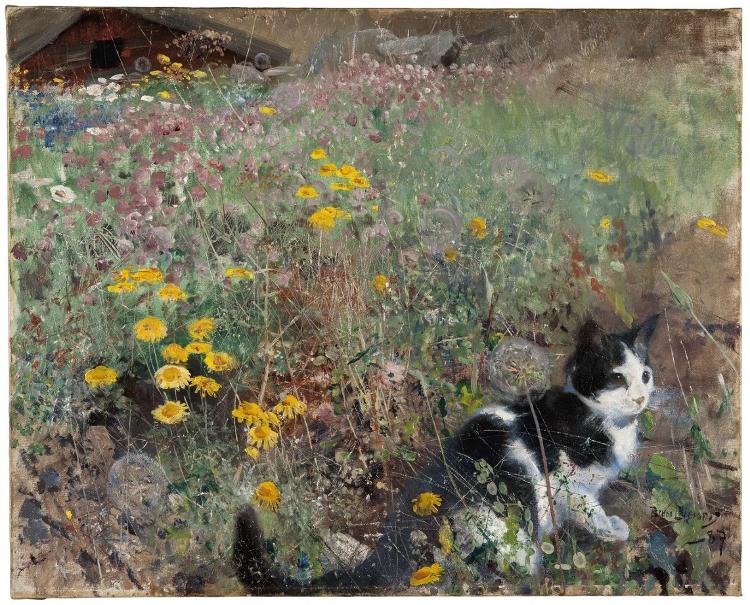

Con mèo trong bụi hoa của Bruno Liljefors. Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia, phạm vi công cộng

Bất chấp các ví dụ tích cực đó, các cơ sở

vẫn còn e ngại với việc cung cấp truy cập đầy đủ tới các bộ sưu tập

được số hóa của họ, chưa nói tới sử dụng lại tự do không mất tiền. Vài

cơ sở chỉ ra rằng họ không có thiện chí từ bỏ đặc quyền giải thích của

họ. Hầu hết các cơ sở thường ủng hộ truy cập mở, nhưng cảm thấy họ cần

đánh giá rủi ro kỹ lưỡng hơn. Họ lo ngại liệu các lợi ích tiềm năng có

thắng được các rủi ro của việc mở ra hay không.

Từng cơ sở có tập hợp các rủi ro và lý lẽ của riêng mình để nói chống lại việc tham gia phong trào đã được mô tả như là Tính mở Trực tuyến Mới trong năm 2015.

Nhưng những lợi ích tiềm tàng của OpenGLAM là nhất quán và có thể được

tóm tắt như là: sự vươn tới rộng hơn, tính trực quan cao hơn, nhiều

người sử dụng hơn và cộng tác tăng cường hơn với các khán thính phòng

của viện bảo tàng.

Liệu điều này có ngụ ý OpenGLAM tự động

“biến đổi cách thức chúng ta kết nối với các khán thính phòng” hay

không, Max Hollein đã nêu? Hãy nhìn sát hơn vào những gì đã xảy ra trước

đó, trong và sau khi Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia đã quyết định triển khai

những gì chúng tôi đã bắt đầu gọi là “Chính sách OpenGLAM” của chúng

tôi.

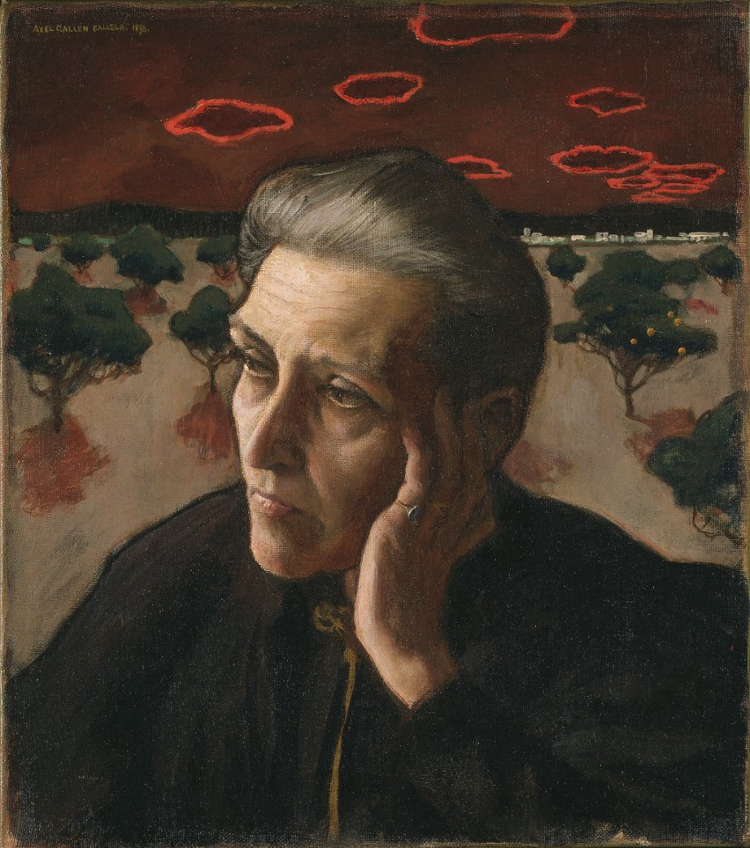

Bà mẹ nghệ sỹ của Akseli Gallen-Kallela. Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia, phạm vi công cộng

Cân bằng rủi ro thiệt hại với lợi ích công cộng

Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia đã tung ra chính

sách OpenGLAM của nó vào năm 2016, theo sau nhiều thảo luận, bao gồm,

nhưng không giới hạn tới: các chi phí hạ tầng kỹ thuật để cung cấp truy

cập tới các bộ sưu tập; thiếu các tài nguyên số hóa và siêu dữ liệu làm

catalog; mất doanh thu bởi việc không có khả năng bán các giấy phép hình

ảnh được nữa và các lo ngại về sử dụng phi đạo đức các tác phẩm nghệ

thuật. Dựa vào nghiên cứu của Simon Tanner, sự mất mát doanh thu đáng sợ

đã được tuyên bố bằng huyền thoại của Merete Sanderhoff vào năm 2013.

Thậm chí đối với Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia điều đó từng đúng rằng viện bảo

tàng đã không còn sinh lợi nhuận bằng việc bán tranh nữa. Tôi sẽ quay

lại câu hỏi không thể tránh khỏi của việc đầu tư vào hạ tầng số, nhưng

muốn bắt đầu bằng việc thảo luận về nỗi sợ hãi bị lạm dụng.

Hầu hết các cơ sở của chúng ta đang cố

gắng làm tốt nhất để trở thành các địa điểm mở và mời chào. Và vẫn còn

46% các công dân chưa tham gia các viện bảo tàng nghệ thuật và thiết kế

đã trích dẫn “Nó không dành cho những ai như tôi” như là một rào cản.

Trong các thảo luận về các giấy phép mở, câu hỏi bị lạm dụng luôn nảy

sinh. Và trong khi tôi đồng ý rằng có lẽ có các bộ sưu tập nhạy cảm

không nên được sử dụng lại mà không có các giới hạn ngoài môi trường khoa học,

khi nói về nghệ thuật, chúng ta nên tự hỏi mình một chính sách cấp phép

đóng cho hình ảnh sẽ truyền đạt được bao nhiêu cho thái độ “bộ sưu tập

này không dành cho ai đó như bạn” trong môi trường số.

Như Hamilton và Saunderson chỉ ra, nếu

bạn đang vật lộn với sự mất kiểm soát, là cực kỳ hữu dụng để phá vỡ “rủi

ro bị lạm dụng” mơ hồ sang các câu hỏi rất chính xác: “Nếu […] kiểm

soát bị mất, điều này sẽ gây hại cho chúng ta như thế nào? Nó sẽ gây ra

thiệt hại vật chất ư? Tính chân thực của thông tin ư?”

Và trong khi nghĩ về sự chân thực, đáng

đặt ra câu hỏi ngược lại: “Liệu việc cấp phép hạn chế có gây thiệt hại

cho chúng ta không, về vật chất, cho công chúng hoặc tính chân thực của

thông tin hay không?”. Là quan trọng để nhớ rằng các giấy phép đóng

không bảo vệ cho sự trông cậy của viện bảo tàng khỏi bị lạm dụng. Tôi

tin tưởng rằng sự thiệt hại dành cho công chúng, vật chất và đặc biệt

cho tính chân thực và khả năng truy xuất thông tin là lớn hơn nhiều nếu

tư liệu đó không được mở ra để sử dụng lại so với rủi ro tiềm tàng bị

lạm dụng. Nếu tư liệu đó không dễ để có thể được sử dụng lại, “sự uyên

thâm [bị] bỏ lại một mình, tri thức không được bảo tồn cho thế hệ sau,

sử dụng sáng tạo các cơ hội số bị bỏ bớt”.

Các giấy phép hạn chế không luôn dừng

được những kẻ xấu khỏi làm nhiều điều xấu với tư liệu của viện bảo tàng,

mà chúng sẽ luôn dừng những người tốt khỏi làm những điều tốt.

May thay, trong sự đổi mới gần 6 năm của

nó, Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia đã nắm lấy quan điểm rằng nếu nó có thể mở

lại viện bảo tàng vật lý cho bất kỳ ai, nó cần đảm bảo rằng các bộ sưu

tập của nó được mọi người nhận ra, trên trực tuyến cũng như trên thực

địa. Berndt Arell, sau này là Tổng Giám đốc, đã công bố chính sách

OpenGLAM của Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia vào tháng 10/2016, nêu:

“Chúng tôi cam kết đáp ứng sứ mệnh của

chúng tôi thúc đẩy nghệ thuật, mối quan tâm về nghệ thuật, và lịch sử

nghệ thuật bằng việc làm cho các hình ảnh từ các bộ sưu tập của chúng

tôi trở thành một phần không thể thiếu của môi trường số ngày nay. Chúng

tôi cũng muốn nhấn mạnh rằng các tác phẩm nghệ thuật đó thuộc về và vì

thế dành cho tất cả chúng ta, bất kể các hình ảnh đó được sử dụng như

thế nào. Chúng tôi hy vọng bộ sưu tập mở của chúng tôi sẽ truyền cảm

hứng cho những sử dụng và diễn giải mới sáng tạo các tác phẩm nghệ thuật

đó”.

Trong khi thời điểm như vậy có vẻ giống

như sự kết thúc của phát triển dài lâu, thì nó chỉ mới là sự khởi đầu.

Theo ý kiến cá nhân tôi, các cơ sở mở nào đang thúc đẩy sự tham gia và

hội nhập không còn có khả năng viện lý nhạy cảm cho các giấy phép hạn

chế được nữa. Mặt khác, tổ chức không tự động trở thành hội nhập chỉ bằng việc áp dụng chính sách truy cập mở.

Như được nêu trước đó, phong trào mở đã

được khởi xướng và nuôi dưỡng bằng sự biến đổi số nói chung mà chúng ta

đang thấy trong xã hội. Không may, biến đổi số, đặc biệt trong môi

trường viện bảo tàng, chủ yếu vẫn còn được hiểu là một vấn đề kỹ thuật,

vấn đề về tối ưu hóa hạ tầng số và tốt nhất - một kênh truyền thông.

Theo cách thức y hệt việc cấp phép mở thường được coi như là vấn đề của

chính sách bản quyền, hạ tầng CNTT, hoặc việc làm catalog siêu dữ liệu.

Trong khi là tự nhiên để bắt đầu thảo luận theo cách này, chúng ta nên

suy nghĩ rằng sự biến đổi này là về con người, không phải về kỹ thuật.

Thách thức thực sự của tính mở là việc

thay đổi thái độ của viện bảo tàng hướng tới những người sử dụng của nó,

bất kể chúng ta đang ở đâu trong quá trình số hóa các bộ sưu tập hoặc

đang làm cho chúng sẵn sàng. Và chỉ bằng cách thay đổi thái độ, những

lợi ích có hứa hẹn hoặc thường được kỳ vọng của chính sách truy cập mở

mới có thể hiện thực hóa được.

Lâu đài Kalmar dưới ánh trăng, Carl Johan Fahlcrantz. Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia, phạm vi công cộng

Việc phát triển truy cập mở ở Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia

Bước đầu tiên và quan trọng nhất của Viện

bảo tàng Quốc gia, đánh dấu khoảng 50.000 hình ảnh bằng giấy phép CC

BY-SA thay vì ©, đã được triển khai hầu như không nhận ra. Chỉ trong năm

2016, khi chúng tôi đã đi từ CC BY-SA sang phạm vi công cộng, và buộc

chính sách mới vào sự cộng tác tích cực với Wikimedia Thụy Điển và cộng

đồng của nó, chúng tôi đã bắt đầu thấy tác động.

Viện bảo tàng đã bắt đầu hiểu rằng việc

đáp ứng sứ mệnh của nó để “cung cấp những cuộc gặp gỡ có ý nghĩa giữa

con người và nghệ thuật” đã không nhất thiết ngụ ý để mọi người tới

viếng thăm tòa nhà hoặc website. Trên thực tế, cơ hội thực sự để làm cho

các bộ sưu tập của viện bảo tàng được biết tới tốt hơn cho một khán

thính phòng rộng lớn hơn từng là xuất bản chúng trên các nền tảng phổ

biến như Wikipedia.

Sự cộng tác của Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia

với Wikimedia Thụy Điển đã bắt đầu ở phạm vi khá nhỏ: 3.000 hình ảnh độ

phân giải cao mô tả các bản vẽ trong bộ sưu tập của Viện bảo tàng Quốc

gia đã được tải lên Wikimedia Commons và siêu dữ liệu liên quan đã được

tải lên Wikidata. Trong vòng một tuần, các hình ảnh đã được sử dụng

trong hơn 100 bài báo và đã được xem 104.000 lần. Tới tháng 3/2019, các

hình ảnh đó đã được hơn 1.800 bài báo sử dụng, và ngày nay chúng có

khoảng 1,5 triệu lần xem mỗi tháng.

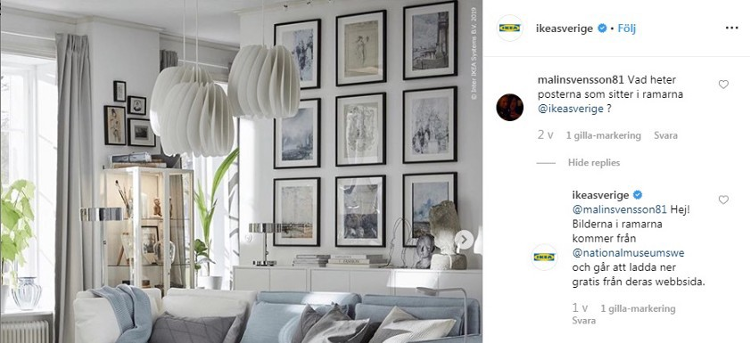

Tin tức về chính sách OpenGLAM của Viện

bảo tàng Quốc gia đã thu hút vài cơ quan truyền thông quốc gia và quốc

tế, nhưng quan trọng nhất nó đã sinh ra sự hiện diện trên các phương

tiện xã hội chúng tôi từng không được thấy trước đó. Sự việc các hình

ảnh được cấp phép mở của Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia đã được sử dụng trong

minh họa của IKEA vào năm 2019 (xem ảnh bên dưới) phục vụ như là ví dụ

về việc bây giờ có nhiều hơn bao nhiêu tác phẩm nghệ thuật của chúng tôi

được bày ra cho công chúng, thậm chí không có sự tham gia tích cực của

viện bảo tàng.

Các bản

in từ bộ sưu tập của Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia được sử dụng để trang trí

trong bài đăng của IKEA vào tháng 3/2019. Người sử dụng hỏi về nguồn của

các hinahf ảnh và câu trả lời của IKEA trỏ chỉ cho người sử dụng trực

tiếp tới website của Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia và trích dẫn các giấy phép

tự do.

Lợi ích xung quanh bộ sưu tập được số hóa

này tới như là sự ngạc nhiên cho vài đồng nghiệp, nhưng nó đã được sử

dụng trong việc tái định vị liên tục thương hiệu của viện bảo tàng và

tông giọng của nhóm truyền thông. Các trao đổi thư điện tử với những

người sử dụng của chúng tôi chỉ ra truy cập mở đã, và thường đang, đáp

ứng được với sự kính trọng và biết ơn như thế nào.

Truyền thông truy cập mở ở Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia

Chúng tôi đã nhận ra rằng chúng tôi đã

cần đồng thanh nhiều hơn về chính sách OpenGLAM của chúng tôi, bên trong

và vượt ra khỏi cơ sở. Sự phát hành mở đã tạo ra mối quan tâm thực sự

nên chúng tôi đã cần đảm bảo rằng nó vẫn là một ưu tiên. Chính sách cấp

phép nhanh chóng trở thành một phần của huấn luyện chung cho các nhân

viên mới. Nó đã nâng cao nhận thức về các nền tảng khác nhau nơi những

người sử dụng có thể tương tác với các bộ sưu tập của Viện bảo tàng Quốc

gia mà bộ sưu tập đó đang không được trưng bày một cách vật lý cho công

chúng.

Vào năm 2017 Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia đã

chuẩn bị khởi xướng lại một website mới, biết rằng nó muốn tung ra vào

thời điểm nơi chưa có tòa nhà viện bảo tàng chính nào để thu hút các

khách viếng thăm tới, và không triển lãm đương thời chính nào. Nội dung

mà chúng tôi đã có cho các kênh số của chúng tôi trước khi viện bảo tàng

được mở lại (vào tháng 10/2018) từng là các câu chuyện về sự cách tân

đang diễn ra và nội dung từ bản thân bộ sưu tập đó. Khi chúng tôi đã

thấy nhiều lượt xem hơn (các viếng thăm lên gấp đôi) tới bộ sưu tập đang

có của chúng tôi trên trực tuyến như là kết quả của chính sách

OpenGLAM, chúng tôi đã nghĩ về nhiều cách thức hơn để làm cho khả năng

truy cập các bộ sưu tập của chúng tôi được nhiều người sử dụng biết tới.

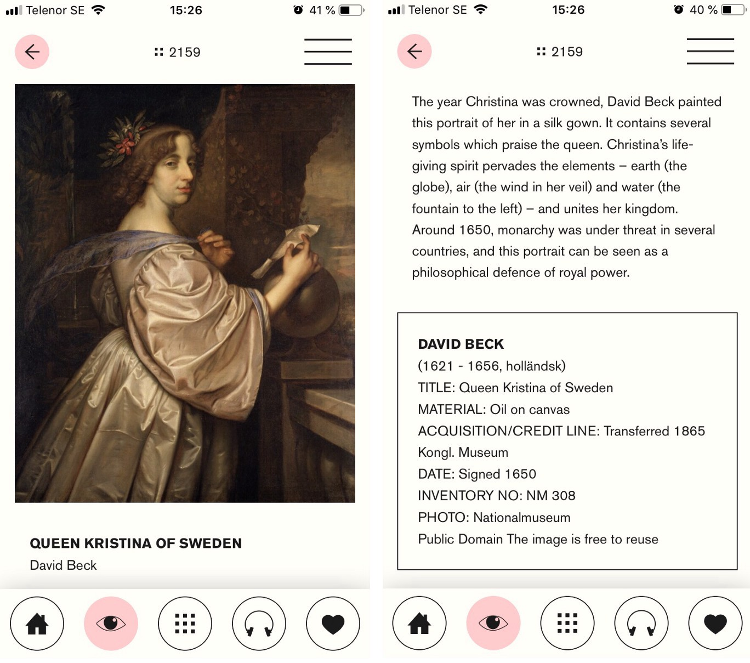

Website viện bảo tàng được khởi xướng

lại, bộ sưu tập trên trực tuyến và ứng dụng mới hướng dẫn khách viếng

thăm đã được phát triển cho việc mở lại viện bảo tàng tất cả đều đặt các

giấy phép mở ở các vị trí nổi bật có chủ ý. Điều này có lẽ giống như

một chi tiết nhỏ nhưng quan trọng để làm cho khái niệm về tính mở được

biết đối với các nhân viên, những người còn chưa làm việc với chủ đề này

trước đó.

Đã trở nên rõ ràng rằng mỗi phát triển

mới và dạng truy cập mới chúng tôi đã trao cho những người sử dụng của

chúng tôi tới bộ sưu tập, chúng tôi có lẽ không có khả năng kiểm soát

hoặc thậm chí dõi theo những gì họ đã làm từ nó. Trong quá trình phát

triển việc trình bày các bộ sưu tập được số hóa thông qua website chính

và ứng dụng hướng dẫn khách thăm quan, chúng tôi đã nhận thức được chúng

tôi cần nêu lại văn bản giấy phép thậm chí với các tuyên bố đơn giản

hơn như “Hình ảnh này là tự do không mất tiền để sử dụng lại”. Trong khi

các giấy phép cung cấp thông tin chính xác và mở rộng trong những gì

người sử dụng có thể có hoặc không sử dụng hình ảnh, chúng tôi đã nhận

thấy rằng người sử dụng nào chưa nhận thức được về khung Creative

Commons có thể không luôn hiểu được các biểu tượng.

Tác phẩm

nghệ thuật được trình bày trong ứng dụng hướng dẫn khách viếng thăm của

Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia, và trong các tua du lịch trên trực tuyến trình

bày các khía cạnh khác nhau của bộ sưu tập.

Một tác

phẩm nghệ thuật được trình bày trong tua trên trực tuyến của Viện bảo

tàng Quốc gia trình bày các khía cạnh khác nhau của bộ sưu tập.

Số hóa và các thách thức của biến đổi số

Cùng lúc, Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia đã chuẩn bị cho việc mở lại một cách vật lý (đã đóng từ năm 2013)

bao gồm trình bày mới các bộ sưu tập sau gần 10 năm nghiên cứu các bộ

sưu tập. Thảo luận xung quanh cách chúng tôi sẽ giám sát việc cập nhật

dữ liệu và sản xuất văn bản khi chuẩn bị cho các triển lãm mới để mở

lại, đã thắp sáng về những gì tôi nghĩ là vấn đề mang tính triệu chứng

khi nói về biến đổi số trong các viện bảo tàng.

Nhiều cơ sở đối mặt với khoảng cách số

giữa quay trình số hóa/làm catalog dài hạn và các nhu cầu ngắn hạn cho

các dự án triển lãm và truyền thông số. Thường thì, nhiều nội dung

thú vị (và thậm chí thường về công nghệ) được sản xuất khi chuẩn bị một

triển lãm hoặc chương trình mới. Nghiên cứu khoa học được triển khai và nhiều sự việc được bổ sung thêm, được kiểm tra 2 lần và được cập nhật. Tư liệu đó được xuất bản và lưu trữ, nhưng thường không có sự kết nối với công việc số hóa và/hoặc làm catalog đang diễn ra.

Số hóa dài lâu, mặt khác, tuân theo tập

hợp các quy định chính xác và thường là tĩnh nhưng nó đôi khi có một

người sử dụng đầu cuối nhất định trong đầu. Nói một cách rõ ràng, số hóa

các bộ sưu tập trong hầu hết các viện bảo tàng có mục tiêu hơi mơ hồ

“số hóa toàn bộ bộ sưu tập”. Nó được cho là để giải quyết tất cả các vấn

đề trong việc xử lý và làm tài liệu và phục vụ cho tất cả các câu hỏi khoa học có

thể nảy sinh trong tương lai. Câu hỏi về chất lượng siêu dữ liệu, nghĩa

là ghi công đúng, ngày tháng, nguồn gốc xuất xứ, .v.v. có mặt ở khắp

nơi và thường giữ cho các cơ sở khỏi việc xuất bản bất kỳ điều gì còn

chưa được kiểm chứng 2 lần.

Ở Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia, thông tin cơ

bản về các phần được số hóa của bộ sưu tập đã được công khai cho công

chúng từ 2010, dù với chất lượng dữ liệu chưa nhất quán, nhưng vài cơ sở

chọn chỉ xuất bản các điểm chính thay vì trao truy cập tới tất cả tài

liệu của họ. Mục tiêu thường là để phân phối siêu dữ liệu chất lượng cao

trong toàn bộ bộ sưu tập, nhưng không giống như các cuộc triển lãm, số

hóa chung trong các viện bảo tàng hiếm khi có thời hạn chót phải đáp ứng

nên nó phát triển rất chậm.

Hầu hết những người chuyên nghiệp trong

viện bảo tàng không hoàn toàn làm việc về các câu hỏi ưu tiên số hóa

thấp hơn so vói tất cả các mối quan tâm khác. Trong hầu hết các trường

hợp điều này dẫn tới ít nhiều các cơ sở dữ liệu nội bộ và trên trực

tuyến được duy trì tốt, theo đó ít thành viên nhân viên có sự hiểu biết

hoặc kiểm soát đầy đủ đối với chúng. Các hệ thống đó thường không đáp

ứng mối quan tâm về khoa học vì

hoặc dữ liệu không có đủ, dữ liệu không đủ chính xác hoặc các hình ảnh

chất lượng không đủ cho hầu hết các tài sản. Mặt khác, thường là khó để

xây dựng cam kết xung quanh chúng, vì các nhân viên truyền thông không

luốn biết những gì đã được số hóa và sẵn sàng, và với chất lượng nào nó

được làm thành tài liệu, hoặc thậm chí điều hướng như thế nào trong hệ

thống nội bộ đó.

John Jennings Esq., anh trai và chị dâu của ông, của Alexander Roslin. Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia, phạm vi công cộng

Thiết kế lại các quy trình quản lý thông tin

Đối với Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia, do đó, nó

đã tập trung vào trình bày mới bộ sưu tập sắp tới trong hầu hết các quy

trình mà thu hẹp được khoảng cách truyền thống đó và để lại toàn bộ cơ

sở sử dụng dữ liệu được cung cấp. Chúng tôi đặt hệ thống quản lý bộ sưu

tập vào trung tâm của việc làm tài liệu và lập kế hoạch trình bày mới và

theo dõi tất cả các bản sửa lỗi, các bản bổ sung và cập nhật trong nó.

Thực tế là mối quan tâm trong bộ sưu tập được số hóa của chúng tôi đã

gia tăng bên ngoài cơ sở đã mở mắt cho chúng tôi về các khả năng mới đối

với tư liệu ngoài sử dụng được dự kiến như các văn bản được in trong

triển lãm sắp tới.

Tất nhiên, sự khởi đầu số hóa chính, việc

làm catalog và việc cập nhật dự án từng không quá nhiều vì chính sách

OpenGLAM. Đã có sự bùng phát về sự cần thiết phải chuyển vật lý 400.000

hiện vật ra khỏi viện bảo tàng trước khi xây dựng mới lại. Dù vậy, không

có mối quan tâm gia tăng xung quanh các bộ sưu tập số của chúng tôi

trên các nền tảng khác nhau, nó có lẽ đã hầu như không có khả năng để

thúc đẩy và thực hiện sự cần thiết về việc không chỉ đăng ký số lượng,

tên và hình ảnh đủ cho kiểm soát công việc hậu cần, mà thậm chí còn giám

sát các mô tả, thông tin còn thiếu, ngày tháng, .v.v. theo cách thức

được tập trung hóa và bền vững.

Khi viện bảo tàng đã đồng ý về cách để xử

lý quy trình cập nhật thông tin và các mô tả đối với hơn 5.000 hiện vật

mà có thể tạo thành trình bày mới của bộ sưu tập trong viện bảo tàng

được mở lại, thông tin này từng truy cập được qua toàn bộ cơ sở và vì

thế hữu dụng cho nhiều mục đích hơn là chỉ trở thành một nhãn mới trong

viện bảo tàng. Việc chuẩn bị các nhãn và các thông tin khác đã được điều

chỉnh với quy trình số hóa, nó đã giúp biến cơ sở dữ liệu quản lý bộ

sưu tập thành kho tri thức đáng tin cậy (với hầu hết các hình ảnh “đủ

tốt” cho tất cả các hiện vật được trưng bày mà có thể được sử dụng như

là nguyên liệu thô cho việc kể chuyện và tham gia trên trực tuyến thông

qua các nền tảng phương tiện khác nhau.

Công ty vui vẻ của Jan Massys. Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia, phạm vi công cộng

Mở truy cập và tâm trí

Có lẽ dường như là lạ lẫn đề khen việc sử

dụng một hệ thống nội bộ hơn 10 năm tuổi như là dấu hiệu của biến đổi

số thành công. Tuy nhiên, công việc thường nhật của chúng tôi từng là về

việc có tri thức sẵn sàng trong cơ sở và tin tưởng các đồng nghiệp với

sự tinh thông khác nhau để xử lý nó có trách nhiệm. Trong một cơ sở

truyền thống như Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia, bước tiến đó từng khó khăn hơn

nhiều nếu chúng tôi đã không có khả năng trỏ tới chính sách OpenGLAM

xuyên khắp các thảo luận. Làm thế nào chúng tôi có thể bảo vệ ý tưởng

của OpenGLAM nếu chúng tôi không chia sẻ thông tin tự do và ở mức giám

sát nội bộ?

Cùng lúc, chúng tôi đã trải nghiệm ở phạm

vi nhỏ về các câu hỏi như làm thế nào để làm cho các hình ảnh sẵn sàng,

làm thế nào để xây dựng các hạng mục đầu vào hấp dẫn cho bộ sưu tập

được số hóa của chúng tôi mà không cần đầu tư quá nhiều vào hạ tầng hoặc

phát triển kỹ thuật. Khi khởi xướng lại website, và phát triển ứng dụng

mới hướng dẫn khách thăm quan, chúng tôi có thể sử dụng các kinh nghiệm

đó để hưởng lợi trong phạm vi rộng lớn hơn. Ứng dụng hướng dẫn khách

viếng thăm của chúng tôi có số lượng người sử dụng và người xem lại tốt

(đối với một ứng dụng của viện bảo tàng), nhưng chuyện vui nội bộ nói

rằng các nhận xét nhiệt tình nhất phải tới từ các đồng nghiệp vì từng

người là quá tự hào về nó.

Trong khi tôi đang không biện hộ rằng bất

kỳ ai trong chúng tôi nên phát triển bất kỳ ứng dụng nào hơn, tôi vẫn

thích nghĩ về câu chuyện đùa đó như là một thành tích. Biến đổi số của

một cơ sở chỉ làm việc với bất kỳ ai tham gia vào. Chúng tôi vẫn cần các

thí điểm phạm vi nhỏ và nhiều dự án hải đăng hơn để hướng dẫn chúng

tôi, nhưng chúng tôi chắc chắn cần thiết lập sự hiểu biết thực sự về

cộng tác số và tính mở bên trong cơ sở ở phạm vi rộng lớn hơn - điều có

thể chỉ làm việc được bằng việc cung cấp dịch vụ số mà hầu hết các thành

viên nhân viên có thể tích cực cảm thấy rằng họ đã đóng góp.

Máng gỗ. Cảnh mùa đông. Từ “Ngôi nhà (26 màu nước)”, của Carl Larsson. Viện bảo tàng Quốc gia, phạm vi công cộng

Các suy nghĩ để kết thúc

Trong khi tôi không đồng tình với hầu hết

các rủi ro (như lạm dụng nội dung) mà đối khi có liên quan tới

OpenGLAM, tôi muốn kết thúc bằng việc chỉ ra rằng có thách thức với

quyết định có lợi cho OpenGLAM. Không cơ sở nào có thể kỳ vọng rằng việc

đồng thuận về một chính sách mở sẽ chỉ “tạo ra” nhiều tương tác hơn với

công chúng, nếu không thay đổi gì hơn.

Là đúng rằng “việc

mở bộ sưu tập ra cung cấp phương tiện cho việc cam kết các sứ mệnh của

cơ sở có liên quan tới việc giáo dục và thông tin cho công chúng, trong

khi mời gọi các thực hành mới cho việc thu hút công chúng đó”, nhưng nó cần công việc tích cực (và được ưu tiên) với các thực hành mới vì cam kết đó và với các cộng đồng có liên quan.

Việc triển khai truy cập mở ngụ ý tiến

hành bước đầu trong chuyển đổi quá độ mà sẽ dẫn tới một môi trường viện

bảo tàng số hơn và cộng tác hơn, cả bên trong và bên ngoài. Sự biến đổi

này đôi khi sẽ gây sợ hãi và đau đớn, nhưng nếu các viện bảo tàng muốn

hưởng lợi từ những lợi ích có liên quan tới OpenGLAM, thì bước đầu tiên

là thừa nhận rằng “việc thiết lập văn hóa trong viện bảo tàng nơi sự

cộng tác mở là chuẩn mức là điều kiện tiên quyết cho bất kỳ sự cộng tác

nào với các cộng đồng” (Seb Chan, 2018).

Cách duy nhất để xây dựng tương lai số

bền vững cho lĩnh vực văn hóa là bằng việc ôm lấy các nguyên lý của tính

mở và sự cộng tác.

Tài liệu

- Aufderheide et al: Copyright, Permissions, and Fair Use among Visual Artists and the Academic and Museum Visual Arts Communities An Issues Report, 2014, available at http://www.collegeart.org/pdf/FairUseIssuesReport.pdf [2019–03–31]

- Dilenschneider, Colleen: They’re Just Not That Into You: What Cultural Organizations Need to Know About Non-Visitors (DATA), 2019, available at http://www.colleendilen.com/2019/02/06/theyre-just-not-that-into-you-what-cultural-organizations-need-to-know-about-non-visitors-data/ [2019–03–31]

- Euler, Ellen: Open Access, Open Data und Open Science als wesentliche Pfeiler einer (nachhaltig) erfolgreichen digitalen Transformation der Kulturerbeinrichtungen und des Kulturbetriebes, in: Herrmann, C. und Pöllmann, L. (eds.): Digitaler Kulturbetrieb, Springer-Nature 2019, available at http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/artdok/6135/1/Euler_Open_access_open_data_open_open_science_als_wesentliche_Pfeiler_2018.pdf [2019–03–31]

- Ellen Euler/Klammt, Anne/ Rack, Oliver: -Willing to share?, 2017, available at https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/content/journal/hintergrund/bereit-zu-teilen [2019–03–31]

- Glasemann, Karin: ‘Offener Zugang als Katalysator für die interne Entwicklung. Wie die Zusammenarbeit mit Europeana, Wikimedia und Linked Open Data Initiativen die Innensicht des Museums verändert.’, presentation given at MAI-Tagung — musuems and the internet — 2016, available at https://mai-tagung.lvr.de/media/mai_tagung/pdf/2016/MAI-2016-Glasemann-DOC.pdf [2019–03–31]

- Hamilton, Gill/Saunderson, Fred: Open Licensing For Cultural Heritage, London 2017

- Kapsalis, Effie: The Impact of Open Access on Galleries, Libraries, Museums, & Archives, 2016, available at https://siarchives.si.edu/sites/default/files/pdfs/2016_03_10_OpenCollections_Public.pdf [2019–03–31]

- Kelcher, Jen: Digital transformation’s people problem. Digital transformation involves technologies and humans. Unfortunately, we tend to ignore the latter when leading change, 2017, available at https://opensource.com/open-organization/17/7/digital-transformation-people-1 [2019–03–31]

- Parry, Ross/ Barnes Sally-Anne/ Kispeter, Erika/ EIkhof, Doris Ruth: Mapping the Museum Digital Skills Ecosystem Phase One Report, Leicester 2018, available at https://doi.org/10.29311/2018.01 [2019–03–31]

- Pekel, Joris: Making a Big Impact on a Small Budget. How the Livrustkammaren och Skoklosters slott med Stiftelsen Hallwylska museet (LSH) Shared Their Collection with the World, 2015, available at https://pro.europeana.eu/files/Europeana_Professional/Publications/Making%20Impact%20on%20a%20Small%20Budget%20-%20LSH%20Case%20Study.pdf [2019–03–31]

- Sacco, Pier Luigi: Culture 3.0: A new perspective for the EU 2014–2020 structural funds programming, 2011, available at http://www.interarts.net/descargas/interarts2577.pdf [2019–03–31]

- Sanderhoff, Merete: ‘Open Images. Risk or opportunity for art collections in the digital age?’, in: Nordisk Museologi, 2013/2, p.131–146, available at https://doi.org/10.5617/nm.3083 [2019–03–31]

- Sanderhoff, Merete: ‘This belongs to you’, in Sanderhoff, Merete (ed.): Sharing is Caring. Openness and Sharing in the Cultural Heritage Sector. Copenhagen 2014, available at https://www.smk.dk/en/article/this-belongs-to-you [2019–03–31].

- Schmidt, Antje: ‘MKG Collection Online: The potential of open museum collections.’, in: Hamburger Journal Für Kulturanthropologie (HJK), 2018/7, 25–39. Available at https://journals.sub.uni-hamburg.de/hjk/article/view/1191 [2019–03–31]

- Stinson, Alex: We applaud the Cleveland Museum of Art’s new open-access policy — and here’s what remains to be done, 2019, available at https://wikimediafoundation.org/2019/01/24/we-applaud-the-cleveland-museum-of-arts-new-open-access-policy-and-heres-what-remains-to-be-done/ [2019–03–31]

- Szraiber, Tanya: The Collection Catalogue as the Core of a Modern Museum’s Purpose and Activities. Keynote at the CIDOC Conference Access and Understanding. Networking in the Digital Era, 6.–11. 9. 2014 in Dresden, available at http://www.cidoc2014.de/images/sampledata/cidoc/papers/Tanya-Szrajber_Keynote.pdf [2019–03–31]

- Tallon, Loic: Introducing Open Access at the Met. THE MET BLOG. 2017, available at https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/digitalunderground/2017/open-access-at-the-met [2019–03–31]

- Tanner, Simon: Open GLAM: The Rewards (and Some Risks) of Digital Sharing for the Public Good, in: Wallace, Andrea/ Deazley, Ronan (eds.), Display At Your Own Risk: An experimental exhibition of digital cultural heritage, 2016, available at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/files/52249306/Display_At_Your_Own_Risk_Publication.pdf [2019–03–31]

- Tanner, Simon: Reproduction charging models & rights policy for digital images in American art museums: A Mellon Foundation funded study. King’s College London, 2004, available at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/reproduction-charging-models--rights-policy-for-digital-images-in-american-art-museums(95d04077-f8ec-4094-b8c1-d585c6b16d9b)/export.html [2019–03–31]

- Visser, Jasper: The future of museums is about attitude, not technology, in: Sanderhoff, Merete (ed.): Sharing is Caring. Openness and Sharing in the Cultural Heritage Sector. Copenhagen 2014, available at https://www.smk.dk/en/article/the-future-of-museums-is-about-attitude-not-technology/ [2019–03–31].

- Wallace, Andrea/McCarthy, Douglas: Survey of GLAM open access policy and practice (started 2018), available at https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1WPS-KJptUJ-o8SXtg00llcxq0IKJu8eO6Ege_GrLaNc/edit#gid=1216556120 [2019–03–31]

- Wallace, Andrea/Pavis, Mathilde: Response to the 2018 Sarr-Savoy Report. Statement on Intellectual Property Rights and Open Access relevant to the digitization and restitution of African Cultural Heritage and associated materials, 2019, available at https://docs.google.com/document/d/1-RIGHXiYjB6nFhzeOn6gHapFL-w9oontJFZfAjlSXkI/ [2019–03–31]

- Weinard, Chad: ‘Maintaining’ the Future of Museums, 2018, available at https://medium.com/@caw_/maintaining-the-future-of-museums-d72631f6905b [2019–03–31]

St.

Catherine of Alexandria, by Artemisia

Gentileschi. Nationalmuseum, Public Domain

“It

is only when cultural institutions start using digital technologies

to foster new research methods and to work collaboratively (…),

that they have truly begun to think digitally.” Professor Ellen

Euler.

The

quote

above summarises my experience of working with digitisation and

digital development at Nationalmuseum, Sweden’s museum for art and

design, over the last seven years. But what does the buzzword

“thinking digitally” mean in a cultural organisation and what has

Open Access got to do with it?

In

the last few years, we have seen a paradigm shift where museums

adjust or re-interpret their mission statements towards encouraging

dialogue and empowering visitors to shape their own cultural

experiences. Ideally, the museum’s role in this scenario shifts

from being primarily a collecting, teaching and preserving

institution to a more fluid role of providing access, enabling

discussion and exchange.

The

wider digital transformation of society partly initiated, and is

fuelling, this transformation of the museum’s role. “Digital”

lowers barriers of access, allows participation and discussion in a

much easier form and, most importantly, it offers the potential for

everyone to build upon the assets and to extend the knowledge that

the museum offers.

However,

this inherent potential does not mean it is used to its full extent.

Although aiming to be an open institution is fundamental to most

museums’ goals, a consensus on how “openness” is best achieved

seems far from being reached.

Lake View at

Engelsberg, Västmanland, by Olof Arborelius. Nationalmuseum, Public

Domain

The

terms on which institutions provide access to their digital

collections, to some extent, express their willingness to cede

control around the stories told about those collections. How do

museums design user experiences around their digitised collections?

How do they encourage — or not encourage — re-use of the digital

assets?

The

movement known as Open

GLAM builds on the premise that cultural heritage data should be

shared openly, i.e. ‘Open

data and content can be freely used, modified, and shared by anyone

for any purpose’.

The principle of openness has been a natural part of web development

long before it reached the cultural heritage sector. For art museums

in particular, Open GLAM means that digitisation should never add a

new copyright — and thus means of control — to cultural works of

art in the public domain.

In

allowing free reuse, digitised collections shift from passive

showcases to become raw material for every user to enjoy, learn from

and build upon. Although there has been resistence

against the Open GLAM movement, the growing number of institutions

adopting open policies is suggestive of a slow but unstoppable

momentum towards greater openness.

Apostle Paul by

Jan Lievens. Nationalmuseum, Public Domain

The

Open GLAM movement in the museum sector was spearheaded in Europe by

the Rijksmuseum already in 2011, and several American institutions

followed suit, with the Smithsonian

Instiution as the latest, most illustrious addition to the Open GLAM

crowd. Already in 2012, the first Swedish museum organisation,

the government agency of Livrustkammaren och Skoklosters slott med

Stiftelsen Hallwylska Museet (LSH), decided to open

its image archive for unrestricted reuse, in collaboration with

Wikimedia Sweden.

The

Danish National Gallery, SMK,

had been a strong

pro-Open GLAM voice since the very beginning. It made its

collection downloadable and reusable on a large scale in 2015.

Shortly afterwards, the Museum

für Kunst und Gewerbe opened its collection for free reuse, the

first German art museum to do so.

These

examples helped to accelerate the discussion towards more openness at

Nationalmuseum, resulting in its Open

GLAM policy announcement in October 2016 — a few month before

the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as one of the heavyweights in the art

museum sector, published its Open

Access initiative in 2017.

When

the Met’s Chief Digital Officer, Loic Tallon, decided

to leave his post in March 2019, the Met’s Director General Max

Hollein lauded his work by framing “the Open Access initiative,

through which the Museum has released over 400,000 images of artworks

in the collection for unrestricted use by any individual around the

world” as one of his most important legacies. The Open Access

initiative, said Hollein, “has transformed how The Met connects

with audiences, and was greatly amplified through building strong

partnerships”.

Cat on a flowery

meadow by Bruno Liljefors. Nationalmuseum, Public Domain

Despite

these positive examples, institutions still shy away from providing

full access to their digitised collections, let alone free reuse.

Some point out that they are not willing to give up their prerogative

of interpretation. Most institutions are generally in favour of open

access, but feel they need a more thorough risk assessment. They

worry whether the potential benefits will outweigh the risks of

opening up.

Every

institution has its own set of risks and arguments that speak against

joining the movement that was described as New

Online Openness in 2015. But the potential benefits of Open GLAM

are consistent and can be summarised as: broader reach, higher

visibility, more users and more intense collaboration with the

museum’s audiences.

Does

this mean Open GLAM automatically “transforms the way we connect

with audiences”, as Max Hollein stated? Let’s have a closer look

at what happened before, during and after the Nationalmuseum decided

to implement what we have come to call our “OpenGLAM-Policy”.

The Artist’s

Mother by Akseli Gallen-Kallela. Nationalmuseum, Public Domain

Nationalmuseum

launched its Open GLAM policy in 2016, following intense internal

discussions, including, but not limited to: costs of technical

infrastructure to provide access to the collections; missing

resources for digitization and metadata cataloguing; loss of income

by not being able to sell image licences anymore and concerns about

morally inappropriate use of the artworks. Based on Simon Tanner’s

research, the feared loss of income was declared a myth by Merete

Sanderhoff in 2013. Even for Nationalmuseum it was true that the

museum was no longer generating profit by selling images. I will come

back to the inevitable question of investing into digital

infrastructure, but want to start by discussing the fear of misuse.

Most

of our institutions are doing their best to be open and inviting

places. And yet 46% of the citizens who do not participate in art or

design museums cited “It’s not for someone like me” as a

barrier. In discussions about open licences the question of misuse

always arises. And while I agree that there might be sensitive

collections that should not be reusable without limits outside a

scientific sphere, when it comes to art, we should question ourselves

how much a closed image licensing policy will communicate an attitude

of “this collection is not for someone like you” in the digital

sphere.

As

Hamilton and Saunderson point out, if you are struggling with the

loss of control, it is extremely helpful to break down the vague

“risk of abuse” to the very precise questions: “If […]

control is lost, how will this damage us? Will it damage the

material? The information’s veracity?”

And

while thinking about veracity, it is worth posing the opposite

question: “Will restrictive licensing damage us, the material, the

public or the information’s veracity?”. It is important to

remember that closed licenses do not safeguard the museum’s

recourses from being misused. I believe that the harm done to the

public, the material and especially to the information’s veracity

and retrievability is far greater if the material is not opened for

reuse than the potential risk of abuse. If the material cannot easily

be reused, “scholarship [is] left undone, knowledge not preserved

for the next generation, creative use of digital opportunities

truncated”.

Restrictive

licences don’t always stop bad people from doing bad stuff with the

museum’s material, but they will always stop good people from doing

good.

Fortunately,

during its almost six-year renovation, Nationalmuseum took the view

that if it was going to reopen a physical museum for everyone, it

needed to make sure that its collections were perceived as

everyone’s, online as well as onsite. Berndt Arell, then Director

General, announced the Nationalmuseum’s Open GLAM policy in October

2016, stating:

“We

are committed to fulfilling our mission to promote art, interest in

art, and art history by making images from our collections an

integral part of today’s digital environment. We also want to make

the point that these artworks belong to and are there for all of us,

regardless of how the images are used. We hope our open collection

will inspire creative new uses and interpretations of the artworks.”

While

such a moment might look like the end of a long development, it was

just the beginning. In my opinion, open institutions which foster

participation and inclusion are no longer be able to sensibly argue

for restrictive licences. On the other hand, an

organisation does not automatically become inclusive just by applying

open access policy.

As

stated earlier, the open movement was initiated and fuelled by the

general digital transformation we are seeing in society.

Unfortunately, digital transformation, especially in the museum

sphere, is still mainly understood to be a technical issue, a problem

about streamlining digital infrastructure and at best — a

communication channel. In the same way, open licensing is often seen

as a matter of copyright policy, IT infrastructure, or metadata

cataloguing. While it is natural to start the discussion this way, we

should be mindful that this transformation is about people, not

techniques.

The

real challenge of openness is changing a museum’s attitude towards

its users, no matter where we are in the process of digitising the

collections or making them available. And it is only by change

attitudes that the promised and often expected benefits of open

access policy can be realised.

Kalmar Castle by

Moonlight, Carl Johan Fahlcrantz. Nationalmuseum, Public Domain

The

Nationalmuseum’s first and most important step, marking around

50,000 images with a CC BY-SA licence instead of ©, went almost

unnoticed. It was only in 2016, when we went from CC BY-SA to Public

Domain, and tethered the new policy to an active collaboration with

Wikimedia Sweden and its community, that we began to see an impact.

The

museum began to understand that fulfilling its mission to “provide

meaningful encounters between people and art” did not necessarily

mean getting people to visit the building or the website. In fact,

the real opportunity to make the museum’s collections better known

to a large audience was to publish them on popular platforms such as

Wikipedia.

Nationalmuseum’s

collaboration with Wikimedia Sweden started at a relatively small

scale: 3000 high-resolution images depicting paintings in the

Nationalmuseum’s collection were uploaded to Wikimedia Commons and

the affiliated metadata was uploaded to Wikidata. Within a week,

images had been used in over 100 articles and had been seen 104,000

times. By March 2019, the images had been used in over 1800 articles,

and today they are viewed approximately 1.5 million times every

month.

The

news of Nationalmuseum’s Open GLAM policy attracted some national

and international media coverage, but most importantly it generated a

presence on social media we had not seen before. The fact that

Nationalmuseum’s openly licensed images were used in an

illustration by IKEA in 2019 (see image below) serves as an example

how much more our artworks are now exposed to the public, even

without the museum actively taking part.

Prints from

Nationalmuseum’s collection are used as decoration in an IKEA post

in March 2019. A user asks for the source of the images and IKEA’s

answer points the user directly to the Nationalmuseum’s website and

cites the free licences.

This

interest around the digitised collection came as a surprise to some

colleagues, but it was used in an ongoing repositioning of the

museum’s brand and tone of voice by the communication team. Email

exchanges with our users show how much open access was, and often

still is, met with awe and thankfulness.

We

realised that we needed to be more vocal about our Open GLAM policy,

inside and beyond the institution. The open release had created

genuine interest so we needed to ensure that it remained a priority.

The licensing policy quickly became a part of general training for

new staff. It raised awareness of the different platforms where users

could interact with Nationalmuseum’s collections without the

collection being physically exhibited to the public.

In

2017 Nationalmuseum was preparing the relaunch of a new website,

knowing that it would launch at a time where there was no main museum

building to attract visitors to, and no major temporary exhibition.

The content that we had for our digital channels before the museum

reopened (in October 2018) were stories about ongoing renovation and

content from the collection itself. When we saw more traffic (visits

doubled) to our existing collection online as a result of the Open

GLAM policy, we were thinking of more ways to make the accessibility

of our collections known to the users.

The

relaunched museum website, collection online and new visitor guide

app which were developed for the museum reopening all put open

licences in deliberately prominent positions. This might seem like a

minor detail but it was important for making the concept of openness

known to staff who had not dealt with this topic before.

It

became evident that with every new development and new form of access

that we granted our users to the collection, we would not be able to

control or even follow up what they made from it. During the

development of presenting the digitised collections via the main

website and the visitor guide app, we realised we needed to rephrase

the licence text to even simpler statements such as “The image is

free to reuse”. While licences provide concise and extensive

information on what the user may or may not use an image for, we

realised that users unaware of the Creative Commons framework would

not always understand the icons.

An artwork

presented in the Nationalmuseum Visitor Guide App, and in online

tours presenting different aspects of the collection.

An artwork

presented in the Nationalmuseum’s online tour presenting different

aspects of the collection.

Simultaneously,

Nationalmuseum was preparing for its physical reopening (having been

closed

since 2013) including new display of the collections after almost

ten years of collections research. The discussion around how we were

going to keep track of updating data and text production when

preparing the new exhibitions for the reopening, shed light on what I

think is a symptomatic problem when it comes to digital

transformation in museums.

Many

institutions are faced with a traditional gap between long-term

digitisation/cataloguing process and the short term needs for

exhibition projects and digital communication.

Often, a lot of amazing content (and often even technology) is

produced when preparing a new exhibition or program. Scientific

research is carried out and a lot of facts are added, double-checked

and updated. The material is published and archived, but often with

no connection to ongoing digitisation and/or cataloguing work.

Long

term digitisation, on the other hand, follows a precise and often

static set of rules but it seldom has a specific end user in mind. To

put it dramatically, collections digitisation in most museums has the

somewhat vague goal to “digitise the whole collection”. It is

supposed to solve all the problems in handling and documentation and

to serve all scientific questions that might arise in the future. The

question of metadata quality, i.e. correct attribution, dates,

provenance etc. is omnipresent and often keeps institutions from

publishing anything which has not been doublechecked.

At

Nationalmuseum, basic information on the digitised parts of the

collection has been exposed to the public since 2010, albeit with

inconsistent data quality, but several institutions choose to only

publish highlights instead of granting access to all their

documentation. The goal is often to deliver high-quality metadata on

the whole collection, but unlike exhibitions, general digitisation in

museums seldom has a deadline to meet so it develops very slowly.

Most

museum professionals not working exclusively in digital prioritise

digitisation questions lower than all other concerns. In most cases

this leads to more or less well-kept internal and online databases,

of which a few members of staff have full understanding or control

over. These systems often fall short for scientific interest as there

is either not enough data, not concise enough data or insufficient

high-quality images for most assets. On the other hand, it is often

hard to build engagement around them, as communications staff do not

always know what has been digitised and available, and in what

quality it is documented, or even how to navigate in the internal

system.

John Jennings

Esq., his Brother and Sister-in-Law, by Alexander Roslin.

Nationalmuseum, Public Domain

For

Nationalmuseum, it was consequently focusing on the upcoming new

display of the collection in almost all processes which closed that

traditional gap and let the whole institution make use of the data

provided. We put the collection management system at the centre of

documenting the planning of the new display and kept track of all

corrections, additions and updates in it. The fact that interest in

our digitised collection had risen outside the institution opened our

eyes for new possibilities for the material apart from the intended

use as printed text in the upcoming exhibition.

Of

course, the initiation of the major digitisation, cataloguing and

updating project was not so much due to the Open GLAM policy. It was

sparked by the necessity to physically move 400,000 objects out of

the museum before the building renovation. Nonetheless, without the

increased interest around our digital collections on various

platforms, it would have been almost impossible to promote and

effectuate the necessity of not only registering a number, title and

image sufficient for logistic control, but to even oversee

descriptions, missing information, dates, etc. in a centralised and

sustainable way.

When

the museum had agreed on how to handle the process of updating

information and descriptions on over 5000 objects which would form

the new presentation of the collection in the reopened museum, this

information was accessible throughout the whole institution and thus

usable for more purposes than just becoming a new label in the

museum. Preparing labels and other information was streamlined with

the digitization process, which helped growing the collection

management database into a reliable knowledgebase (with mostly “good

enough” images for all exhibited objects) that could be used as raw

material for online storytelling and engagement via different media

platforms.

A Merry Company

by Jan Massys. Nationalmuseum, Public Domain

It

might seem strange to praise the use of a more than 10-year-old

internal system as a sign of successful digital transformation.

However, our working routine was about having knowledge available

within the institution and to trust colleagues of different expertise

to handle it responsibly. In a traditional institution like

Nationalmuseum, that step had been a lot harder if we had not been

able to point to the Open GLAM policy throughout discussions. How

could we champion the idea of Open GLAM if we do not share

information freely and at eye-level internally?

At

the same time, we had been experimenting at small scale on questions

like how to make images available, how to build engaging entries to

our digitised collection without investing too much on infrastructure

or technical development. When relaunching the website, and

developing a new visitor guide app, we could use those experiences to

benefit on a larger scale. Our visitor guide app has good user

numbers and reviews (for a museum app), but an internal joke claims

that the most enthusiastic remarks must come from colleagues because

everyone is so proud of it.

While

I am not advocating that any of us should develope any more apps, I

still like to think of that joke as an achievement. Digital

transformation of an institution only works with everyone on board.

We still need small-scale experiments and more lighthouse projects to

guide us, but we definitely need to settle a genuine understanding of

digital collaboration and openness inside the institution at a larger

scale — which might just work by providing a digital service which

most staff members can actively feel that they contributed to.

The Timber

Chute. Winterscene. From “A Home (26 watercoulours)”, by Carl

Larsson. Nationalmuseum, Public Domain

While

I disagree with most of the risks (such as content misuse) that are

sometimes associated with Open GLAM, I want to end by pointing out

that there is a challenge with a decision in favour of Open GLAM. No

institution can expect that agreeing on an open policy will just

“create” more interaction with the public, if nothing else

changes.

It

is true that “opening

collections provides a vehicle for engaging institutional missions

related to educating and informing the public, while inviting new

practices for engaging that public”, but it needs active (and

prioritised) work with those new practices for engagement and with

the related communities.

Implementing

open access means taking the first step in a transition that will

lead to a more digital and more collaborative museum environment,

externally and internally. This transition will at times be

frightening and painful, but if museums want to profit from the

benefits associated with Open GLAM, the first step is to acknowledge

that “setting a culture in the museum where open collaboration is

the norm is a prerequisite for any collaboration with other

communities” (Seb

Chan, 2018).

The

only way to build a sustainable digital future for the cultural

sector is by embracing the principles of openness and collaboration.

Aufderheide

et al: Copyright, Permissions, and Fair Use among Visual Artists and

the Academic and Museum Visual Arts Communities An Issues Report,

2014, available at

http://www.collegeart.org/pdf/FairUseIssuesReport.pdf

[2019–03–31]

Dilenschneider,

Colleen: They’re Just Not That Into You: What Cultural

Organizations Need to Know About Non-Visitors (DATA), 2019, available

at

http://www.colleendilen.com/2019/02/06/theyre-just-not-that-into-you-what-cultural-organizations-need-to-know-about-non-visitors-data/

[2019–03–31]

Euler,

Ellen: Open Access, Open Data und Open Science als wesentliche

Pfeiler einer (nachhaltig) erfolgreichen digitalen Transformation der

Kulturerbeinrichtungen und des Kulturbetriebes, in: Herrmann, C. und

Pöllmann, L. (eds.): Digitaler Kulturbetrieb, Springer-Nature 2019,

available at

http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/artdok/6135/1/Euler_Open_access_open_data_open_open_science_als_wesentliche_Pfeiler_2018.pdf

[2019–03–31]

Ellen

Euler/Klammt, Anne/ Rack, Oliver: -Willing to share?, 2017, available

at

https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/content/journal/hintergrund/bereit-zu-teilen

[2019–03–31]

Glasemann,

Karin: ‘Offener Zugang als Katalysator für die interne

Entwicklung. Wie die Zusammenarbeit mit Europeana, Wikimedia und

Linked Open Data Initiativen die Innensicht des Museums verändert.’,

presentation given at MAI-Tagung — musuems and the internet —

2016, available at

https://mai-tagung.lvr.de/media/mai_tagung/pdf/2016/MAI-2016-Glasemann-DOC.pdf

[2019–03–31]

Kapsalis,

Effie: The Impact of Open Access on Galleries, Libraries, Museums, &

Archives, 2016, available at

https://siarchives.si.edu/sites/default/files/pdfs/2016_03_10_OpenCollections_Public.pdf

[2019–03–31]

Kelcher,

Jen: Digital transformation’s people problem. Digital

transformation involves technologies and humans. Unfortunately, we

tend to ignore the latter when leading change, 2017, available at

https://opensource.com/open-organization/17/7/digital-transformation-people-1

[2019–03–31]

Parry,

Ross/ Barnes Sally-Anne/ Kispeter, Erika/ EIkhof, Doris Ruth: Mapping

the Museum Digital Skills Ecosystem Phase One Report, Leicester 2018,

available at https://doi.org/10.29311/2018.01

[2019–03–31]

Pekel,

Joris: Making a Big Impact on a Small Budget. How the Livrustkammaren

och Skoklosters slott med Stiftelsen Hallwylska museet (LSH) Shared

Their Collection with the World, 2015, available at

https://pro.europeana.eu/files/Europeana_Professional/Publications/Making%20Impact%20on%20a%20Small%20Budget%20-%20LSH%20Case%20Study.pdf

[2019–03–31]

Sacco,

Pier Luigi: Culture 3.0: A new perspective for the EU 2014–2020

structural funds programming, 2011, available at

http://www.interarts.net/descargas/interarts2577.pdf

[2019–03–31]

Sanderhoff,

Merete: ‘Open Images. Risk or opportunity for art collections in

the digital age?’, in: Nordisk Museologi, 2013/2, p.131–146,

available at https://doi.org/10.5617/nm.3083

[2019–03–31]

Sanderhoff,

Merete: ‘This belongs to you’, in Sanderhoff, Merete (ed.):

Sharing is Caring. Openness and Sharing in the Cultural Heritage

Sector. Copenhagen 2014, available at

https://www.smk.dk/en/article/this-belongs-to-you

[2019–03–31].

Schmidt,

Antje: ‘MKG Collection Online: The potential of open museum

collections.’, in: Hamburger Journal Für Kulturanthropologie

(HJK), 2018/7, 25–39. Available at

https://journals.sub.uni-hamburg.de/hjk/article/view/1191

[2019–03–31]

Stinson,

Alex: We applaud the Cleveland Museum of Art’s new open-access

policy — and here’s what remains to be done, 2019, available at

https://wikimediafoundation.org/2019/01/24/we-applaud-the-cleveland-museum-of-arts-new-open-access-policy-and-heres-what-remains-to-be-done/

[2019–03–31]

Szraiber,

Tanya: The Collection Catalogue as the Core of a Modern Museum’s

Purpose and Activities. Keynote at the CIDOC Conference Access and

Understanding. Networking in the Digital Era, 6.–11. 9. 2014 in

Dresden, available at

http://www.cidoc2014.de/images/sampledata/cidoc/papers/Tanya-Szrajber_Keynote.pdf

[2019–03–31]

Tallon,

Loic: Introducing Open Access at the Met. THE MET BLOG. 2017,

available at

https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/digitalunderground/2017/open-access-at-the-met

[2019–03–31]

Tanner,

Simon: Open GLAM: The Rewards (and Some Risks) of Digital Sharing for

the Public Good, in: Wallace, Andrea/ Deazley, Ronan (eds.), Display

At Your Own Risk: An experimental exhibition of digital cultural

heritage, 2016, available at

https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/files/52249306/Display_At_Your_Own_Risk_Publication.pdf

[2019–03–31]

Tanner,

Simon: Reproduction charging models & rights policy for digital

images in American art museums: A Mellon Foundation funded study.

King’s College London, 2004, available at

https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/reproduction-charging-models--rights-policy-for-digital-images-in-american-art-museums(95d04077-f8ec-4094-b8c1-d585c6b16d9b)/export.html

[2019–03–31]

Visser,

Jasper: The future of museums is about attitude, not technology, in:

Sanderhoff, Merete (ed.): Sharing is Caring. Openness and Sharing in

the Cultural Heritage Sector. Copenhagen 2014, available at

https://www.smk.dk/en/article/the-future-of-museums-is-about-attitude-not-technology/

[2019–03–31].

Wallace,

Andrea/McCarthy, Douglas: Survey of GLAM open access policy and

practice (started 2018), available at

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1WPS-KJptUJ-o8SXtg00llcxq0IKJu8eO6Ege_GrLaNc/edit#gid=1216556120

[2019–03–31]

Wallace,

Andrea/Pavis, Mathilde: Response to the 2018 Sarr-Savoy Report.

Statement on Intellectual Property Rights and Open Access relevant to

the digitization and restitution of African Cultural Heritage and

associated materials, 2019, available at

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1-RIGHXiYjB6nFhzeOn6gHapFL-w9oontJFZfAjlSXkI/

[2019–03–31]

Weinard,

Chad: ‘Maintaining’ the Future of Museums, 2018, available at

https://medium.com/@caw_/maintaining-the-future-of-museums-d72631f6905b

[2019–03–31]

Dịch: Lê Trung Nghĩa

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét

Lưu ý: Chỉ thành viên của blog này mới được đăng nhận xét.